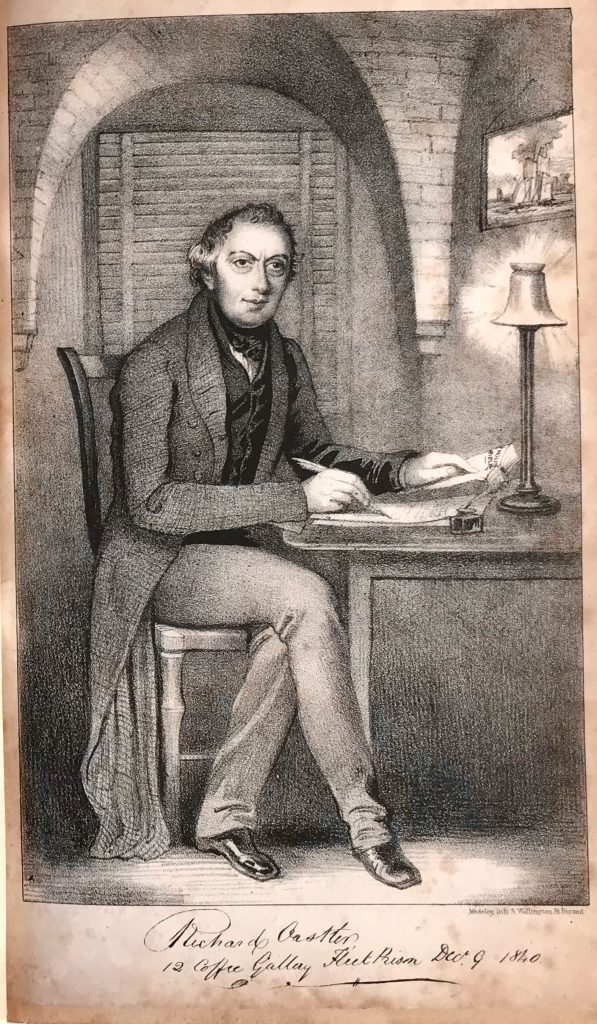

Richard Oastler, 1789 – 1861

Richard Oastler made his name as a passionate opponent of a system which forced children as young as seven to work long hours in the West Yorkshire textile mills. But though courted by the Chartist leadership and an ally to many, he was an opponent of universal suffrage.

Richard Oastler was revered as the Factory King by radicals in the North of England for his involvement in the Ten Hours Movement and opposition to the New Poor Law. But though many of his most ardent supporters would adopt the People’s Charter as it emerged from the working-class campaigns of the 1830s, Oastler himself remained a ‘Church and King’ ‘Ultra Tory’, opposed to parliamentary reform and retaining a deep admiration for the Duke of Wellington and his opposition to radical causes.

Despite this, there was no break between Oastler and his factory reform allies who turned Chartists, and when in 1838 his associate Joseph Rayner Stephens was arrested for unlawful assembly, Oastler played a leading part in raising funds for his defence. And though Oastler remained actively hostile to universal suffrage, Feargus O’Connor, who sought to inherit Oastler’s mantle as the leading figure in Northern radicalism, and the popular support that came with it, went as far as to include the Factory King’s portrait among the series of engraved prints given away with the Northern Star.

Factory reform and the Ten Hours Movement

Born at Leeds on 20 December 1789, Richard Oastler was the youngest of ten children, whose father Robert, a linen merchant, became steward for Thomas Thornhill, the absentee landlord of the large Fixby estate near Huddersfield and of nearby Calverley. As a young man, he worked as a commission agent, and land agent, acting from time to time for his father at Fixby, including in 1812 when he organised measures to protect against possible Luddite attacks in the locality.

By 1821, he had succeeded his father at Fixby, managing rents of £18,000 a year for an annual salary of £300. Already well-known as an advocate for the abolition of slavery, in 1830 he experienced a sudden conversion to factory reform, which in practical terms meant legal limits on children’s working time and safety measures within the mills. Oastler was apparently told by John Wood, a reforming Bradford manufacturer about the evils of children’s employment in the area, took up the cause, and gave a promise to devote himself to their removal.

He would later recall: ‘I had lived for many years in the very heart of the factory districts; I had been on terms of intimacy and of friendship with many factory masters, and I had all the while fancied that factories were a blessing to the poor’. Oastler wrote a letter to the Whig Leeds Mercury headed ‘Slavery in Yorkshire’ in which he highlighted the plight of ‘thousands of little children, both male and female, but principally female, from SEVEN to fourteen years of age [who] are daily compelled to labour from six o’clock in the morning to seven in the evening…’. Oastler highlighted the hypocrisy of middle-class campaigners then flocking to support the fashionable call for the abolition of slavery in the West Indies, by drawing parallels between Black slaves in the British colonies and ‘British Infantile Slavery’ (Leeds Mercury, 16 October 1830, p4).

Oastler won considerable local support, and gave his backing to a Bill put forward in Parliament by the Whig reformer John Cam Hobhouse in 1831 to extend the Factory Act to a wider range of textile industries. This was opposed by a meeting of Yorkshire mill-owners and by the Leeds Mercury, which refused to publish Oastler’s letter of support in full, prompting him to turn in future to the Tory Leeds Intelligencer as an outlet for his writing. When the Bill fell after a general election was called, a deputation from the Huddersfield Short Time Committee made up of trade unionists and radicals met Oastler and agreed a ‘Fixby Hall Compact’ to work together despite differences on other issues.

Hobhouse reintroduced his Bill after the election, but it passed only after being stripped of its most important provisions. Short time committees in the Yorkshire mill towns then called mass meetings to support a further attempt at legislation, with Oastler gaining a reputation as an accomplished popular orator. The only outcome, however, was the Factory Act of 1833, which proved highly unsatisfactory – and in any case gave mill-owner magistrates the power to hear cases, making successful prosecutions unlikely.

When agitation revived in 1836, however, Oastler succeeded in alienating more squeamish supporters of the Ten Hour Movement by advocating during a meeting at Blackburn that children should be taught to sabotage machinery. The Leeds Intelligencer stopped publishing his letters, and the social reformer Lord Ashley broke with Oastler; and though the radical industrialist MP John Fielden and the short time committees stood by him, Oastler’s health broke down, and in January 1837 he was unable to address a meeting in Manchester as ‘his exertions on behalf of the factory slave had brought him to the edge of the grave’ (Morning Chronicle. 10 January 1837, p2).

Opposition to the New Poor Law

Oastler was not incapacitated for long. A fortnight later, he spoke at a mass meeting in Huddersfield urging his supporters to resist the implementation of the New Poor Law and its workhouse system. Implemented first in the Southern counties of England, the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 had brought about significant reductions in spending on poor relief, and by January 1837 plans were in hand to set up poor law unions in the West Riding.

Facing pressure from his employer at Fixby Hall, Oastler would initially play little active part in resisting these measures. But many of those who had been active in the Ten Hours Movement turned their efforts to this more immediately pressing concern, organising protests, and attempting to disrupt meetings of local poor law boards. In June 1837, Oastler was among the organisers of an attempt to picket Huddersfield Poor Law Guardians which turned violent when the guardians refused to receive a deputation. Oastler attempted to calm the crowd, but to little effect. There was further violence that summer at election hustings in Huddersfield and Wakefield when Oastler, who was contesting the seat, fell behind in the poll. The Riot Act read and the cavalry sent in to restore order.

Downfall and imprisonment

The following year, Thornhill dismissed Oastler from the stewardship of Fixby Hall. Oastler’s supporters claimed that he had been sacked for opposing ‘Whig tyranny’. They organised a procession to accompany Oastler as he left the estate, and launched a testimonial fund to help him financially. The medal shown here is a surviving souvenir of that event. Thornhill, however, was offended at being portrayed as a tyrant, and issued a letter asserting that Oastler had been sacked for neglecting his duties and using his employer’s money for his own purposes.

Thornhill then took Oastler to court for repayment of the disputed sum of £2,600, and ensured that the case would be heard in Middlesex so that Oastler could not call his numerous Yorkshire supporters as witnesses. Scorning the advice of his lawyers to declare himself bankrupt and so avoid imprisonment, Oastler was found to be in default of his debts, and in December 1840 he was incarcerated in the Fleet Prison, where he would remain until February 1844.

During his time behind bars, Oastler wrote the Fleet Papers, a series of weekly letters ostensibly to his former employer, that were published for 2d, giving him a small income. But, the historian G.D.H Cole has noted: ‘He was a speaker and organiser of immense energy, and not by instinct a writer. The Fleet Papers were bought by his admirers; but they did not exert much influence.’ The Oastler Testimonial Fund was turned into a Liberation Fund. By January 1844 it stood at £2,000, but Oastler’s debts had risen to £3,200. Amid fears for his health, wealthy donors guaranteed the difference to ensure his release.

Oastler’s final years

Once freed, Oastler returned to the Ten Hours campaign, and would continue to speak from the platform at public meetings for much of the remainder of his life. But this was now a more respectable cause, and Oastler neither as fiery a speaker nor as prominent a feature of the campaign as he had once been. Having largely missed out on Chartism at its height and ceded the role of leader of working-class radicalism in the North to Feargus O’Connor during his absence, Oastler was safely absorbed into the Chartist pantheon despite his opposition to its political demands. And when he launched a small publication titled The Home in 1851 to argue his unique brand of Tory paternalism, it made little impact on his reputation for good or ill.

Oastler died in 1861. While visiting friends in Yorkshire, he was taken ill at Harrogate, and died there on 8 August. He was buried in the family vault at St Stephen’s Church in Kirkstall, Leeds. Although he had wanted a private funeral, many of his old short time comrades attended and at their insistence the coffin was carried by twelve factory workers.

Remembering Richard Oastler

There is a small, easily overlooked plaque on an external wall of St Stephen’s which reads: ‘Beneath this arch is the grave of Richard Oastler’. A more recent Leeds Civic Trust blue plaque has been installed in St Peter’s Square in Leeds to mark his birthplace. And he is commemorated, too, by a bronze statue in Bradford. First erected in 1869 in Forster Square and unveiled by Lord Shaftesbury, it stands today in Oastler Square.

G.D.H Cole included Oastler in his twelve Chartist Portraits as ‘one of the makers of Chartism’. But he judged that the Factory King or King of the Factory Children was ‘never a Chartist’, pointing out that he had argued in Henry Hetherington’s Twopenny Dispatch in 1835 that ‘if it [universal suffrage] were the law of the land next week, it would in a very short time produce “universal confusion”.’ Nonetheless, wrote Cole, Oastler had earned himself his place in the Chartist story: ‘For his eloquence and energy both made the factory agitation the powerful thing that it became, and roused the North to that fury of protest against the Malthusian Poor Law which his enforced removal from Yorkshire in 1838 handed over ready made to Fergus O’Connor as the instrument of the chartist campaign.’

The entry for Oastler in the Biographical Dictionary of Modern British Radicals described him as ‘this emotional leader of the masses’, noting: ‘He played the part of a paternalistic squire, with “the Altar, the Throne and the Cottage” for his motto, emphasized the importance of the old community and stratified groups, and regretted that the new industrialism had destroyed the bond of affection between workers and their employers.’ And it notes that he ‘tended to support politicians solely on the basis of how they felt about specific issues which passionately concerned him.’ This allowed him in the Fixby Hall compact to work with democrats and others with whom he disagreed to achieve the ‘specific goal’ of factory reform.

More recently, and in marked contrast to Cole, Dr Matt Roberts has argued that Oastler was, ‘at best, a quixotic Tory’; but that as a figure in the Chartist pantheon with genuinely radical strands to his ideology, he was ‘a Chartist in all but name’.

Notes and sources

The Fleet Papers, by Richard Oastler (Vincent Torras & Co, 1841)

Chartist Portraits, by G.D.H Cole (Macmillan, 1941).

‘Richard Oastler and the Chartists’ in Chartism, Commemoration and the Cult of the Radical Hero, by Matt Roberts (Routledge, 2019).

Dictionary of National Biography, volumes 1-12 p738, on Ancestry (accessed 15 December 2024).

‘Oastler, Richard (1789-1861)’ by Henry Weisser in Biographical Dictionary of Modern British Radicals, vol II, 1830-1870 (Harvester Press, 1984).

Workers of Their Own Emancipation: Working Class Leadership and Organisation in the West Riding Textile District, 1829-1839, by John Sanders (Breviary Stuff, 2024).