John Ardill, 1811 – 1869

For more than a decade, John Ardill was Feargus O’Connor’s discreet, hard-working clerk. He was business manager of the Northern Star from its launch, kept the accounts of the Chartist hardship funds and appeals, and was publisher Joshua Hobson’s reliable deputy in West Riding politics.

Outside Leeds, most Chartists would barely have heard of him, if at all; for them, his role was to sit in the Star’s Leeds office and process the bills that came in from suppliers, pay in subscriptions to the bank, and deal calmly and efficiently with the Post Office when bundles of papers failed to arrive.

But all that came to a sudden and explosive end in the autumn of 1847, leading to allegations and counter-allegations of fraud, a libel case, and Ardill’s departure from the movement.

Early life

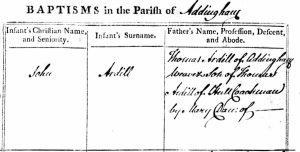

Ardill was born at Addingham near Leeds on 18 November 1811. His father Thomas was a weaver, and his mother Martha the daughter of a woolcomber.1 But his was not entirely a rags-to-riches story. As his friend Joshua Hobson would later recount, Hobson’s father was in a position of trust and responsibility, as overseer at the Burley Mill operated by the Whiteacre family, and his mother ‘had the disposing of all the milk from the Whiteacres’ extensive farms’.2

According to Hobson, Ardill served an eight-year apprenticeship as an iron moulder at Burley Mill. Leaving Burley for Leeds at the age of 21, he turned his hand to brass moulding in a machine shop, where he succeeded in improving the factory processes there such that he was able to earn £3 a week – a significant sum for a working man. In the evenings, he also became secretary to a number of ‘money clubs’, keeping their accounts and earning further small sums for himself. And he lived frugally, spending no more than 9 shillings a week.

‘By these means, John Ardill had, by the latter end of 1837, realised upwards of £500, though he entered Leeds, in 1832, with but 30s in his pocket,’ wrote Hobson.

Hobson and the Northern Star

O’Connor had come across Ardill over his work on behalf of the money clubs, and in the summer of 1837 introduced him to Hobson. According to Hobson, when O’Connor was unable to come up with the cash needed to get the Northern Star off the ground, Ardill lent him enough to pay the wages of the men fixing up the print shop for the new paper. Hobson and Ardill clearly got on well, and within a few weeks Ardill was lodging at Hobson’s house, rent free on condition that he help out in Hobson’s shop during the day. Soon afterwards, O’Connor appointed him as the Star’s bookkeeper and cashier on a salary that matched his previous earnings as a brass founder.

Ardill’s name first appears publicly in relation to the Chartist cause at about the same time, when the Leeds Working Men’s Association was formed at a meeting where the speakers included London ‘missionaries’ John Cleave and Henry Vincent. Hobson, who had been instrumental in organising the event, was elected chairman and Ardill became one of seven members of the provisional committee established to produce a rule book and organise the new body.3

Ardill’s name appeared regularly in the Northern Star, though always as a point of contact rather than for any political contributions he may have made. Based on the contexts in which his name appears, his duties included receiving bills from suppliers and payments from subscribers, chasing up deliveries of the Star that had gone astray in the post, and liaising with the engraver when the paper produced commemorative portraits. In 1840, when O’Connor was in imprisoned at York Castle for seditious libel, Ardill, Hobson and the paper’s then editor William Hill were permitted to visit him for brief business meetings (NS, 20 February 1841, p4).

By then, Ardill was a married man. On 7 November 1840, giving his address as Market Street (the location of the Star and of Hobson’s business), he married Jane Pearson, the daughter of a tailor, at St Peter’s in Leeds.4 Ardill gave his occupation in the parish register as book-keeper, though O’Connor always referred to him as ‘my clerk’, and in practice he appears to have managed the paper’s business affairs and had wider responsibilities.

Reporting on the activities of nine funds for victims, their families and other Chartist causes, O’Conor remarked that one recipient, ‘very properly thanked Mr Ardill for his trouble, and, bear in mind, every additional fund attaches additional labour to him, without any additional emolument’ (NS, 22 May 1841, p5).

Leeds politics and the land

The following year, Ardill took a step into Leeds politics. When a ratepayers’ meeting was held in the vestry of the parish church to elect nineteen members to the town’s Improvement Commission, Ardill was one of the twelve-strong Chartist slate to be voted in. The remaining seven seats stayed with existing Whig-Liberal members of the Commission, while a Tory slate put forward by a ‘conservative operative’ was rejected outright.

The Whiggish Leeds Mercury was outraged. It named William Hick, the secretary of Leeds Total Abstinence Charter Association and author of Chartist Songs5, as the leader of the Chartist faction at the meeting. Hicks, it claimed, had ‘acted as fugleman, and gave the signal to the crowd when they were to hold up their hands and when they were to keep them down. A great number of them voted in total ignorance of the politics of the parties chosen, and to suppose for a moment that the election which has taken place is anything like an indication of the opinion of a majority of the rate-payers would be a gross absurdity’ (Leeds Mercury, 8 January, 1842, p8).

The Northern Star predictably saw things rather differently, declaring that the seven survivors from the old commission were ‘the most liberal of the lot’. It reported that: ‘For each name proposed by Mr Hick, nearly every hand in the assembly was held up, while for “Morgan’s list”, (the concoction of the Corn Law League and the Fox and Goose Club) not above thirty or forty were held up for any one.’ It added: ‘The united Whig-Rads had no chance.’

Following his election, Ardill served as one of the town’s highway surveyors, and on a subcommittee set up to scrutinise the money spent before the election on the town’s Improvement Bill, both of which would have made use of his experience in financial affairs. The first mention of a home address for Ardill other than Hobson’s house is in the summer of 1842, when a legal notice carried in the Northern Star puts him at Burley Place, Headingley (NS, 13 August 1842, p8). He appears to have returned to his home village.

That autumn, Ardill was present when Manchester police arrived at the Star’s office with its editor, William Hill, in custody. Hill had been arrested in the street after speaking at a meeting in the town. An Inspector Taylor told Hobson that Hill had a set of keys in his possession that he said were for boxes and drawers in the office, and demanded to be able to open them. Hobson stood his ground, asserting that the locked drawers and boxes were his property, and that he would not allow access without a search warrant. Any documents they contained ‘are no more his, than the books belonging to the establishment are the property of the Clerk there (pointing to Mr Ardill,) who has the charge of them,’ he insisted (NS, 1 October 1842, p1).

Shortly before O’Connor moved the Northern Star from Leeds to London, he gave an interesting insight into Ardill’s life outside the office. Writing on his pet topic of land reform, O’Connor revealed: ‘Mr John Ardill, my clerk, holds fourteen acres under Mr Beckett, MP for Leeds; for which he pays rent and taxes £6 per acre.’ He went on: ‘There is now on this farm of fourteen acres, eleven milch cows, six heifers, one horse, twenty-two pigs, forty rabbits, nineteen hens, twenty-five tons of hay, one acre of potatoes, half an acre of Swedish turnips, and half an acre of garden. Mr Ardill employs one man through the year at £1 a week, and a lad at 12s a week: and the farm is by no means in good condition yet. It can be made to do more than three times as much as it has done.’

O’Connor’s denunciation

Ardill stayed in Leeds after the paper moved south in November 1844, but continued to work as its business manager, as clerk to O’Connor, and – by virtue of working for O’Connor – on behalf of the land company and land bank. The following year, O’Connor dismissed Hobson as editor for neglecting his duties, but the assiduous Ardill kept his job.

All that came to an end in the autumn of 1847 when Hobson wrote to the Liberal Manchester Examiner to accuse O’Connor of having siphoned money from the Northern Star and into his own accounts, and Alexander Somerville, a journalist who wrote under the pen name ‘The Whistler at the Plough’, published a series of allegations in the Manchester Examiner about Feargus O’Connor’s handling of the land company’s finances.

O’Connor hit back at a public meeting, defending his honour and his record of spending his own money to support the Chartist cause (NS, 30 October 1847, p1). But O’Connor saw enemies everywhere; if Hobson had made the accusations, then Ardill must also have been involved. In a long, blustering justification of his actions, he accused Hobson and Ardill of falsifying the accounts, defrauding the Northern Star, and by extension the whole Chartist movement, and of enriching themselves in the process.

Ardill’s deputy, William Rider, an O’Connor loyalist who was introduced to the meeting as the paper’s new clerk, repeated the allegations, and went further to claim that Hobson and Ardill had systematically cooked the books since the paper’s inception a decade earlier, and that he had been aware of this all along. He had failed to mention this to O’Connor previously only because he knew that O’Connor trusted the two men totally.

A furious Hobson defended himself and Ardill at length in the Manchester Examiner, telling a version of the Northern Star’s origin story that painted O’Connor as a man long on promises and short on cash, constantly cadging money from one political venture to pay off the debts of another. In this he was probably correct. O’Connor burned through his inherited wealth, selling land and property to pour into his political activities; and he was a generous supporter of the victims of oppression and their families. But if he ever had money to hand, he would spend it on good causes even knowing that there were bills falling due soon; and he seemed incapable of drawing a distinction between his own finances and those of the organisations he was involved with.

Both Hobson and Ardill issued writs for libel. O’Connor backed down, retracted his accusations and apologised, but almost immediately repeated the allegations. He would end up paying Hobson and Ardill damages and legal costs (NS, 18 December 1847, p1).

Life after Chartism

Ousted from the Chartist movement and from his job, Ardill set up in business on his own account. In the 1851 census, he declared his occupation as ‘card maker (employing 4 men + 1 woman). Farmer of 12 acres employing two men’. In other words, he manufactured the ‘cards’ that set the patterns made by looms. A decade later, still living at Burley Place with his wife and six children, he described himself as ‘clasp manufacturer employing one man, 1 woman 3 boys and 2 girls and farmer of 12 acres employing 2 men’. Jane Ardill gave her occupation as ‘farmer’s wife’.

Ardill obviously did well in business. In addition to the main house at Burley Place, which Ardill owned freehold and which qualified him for the vote, rate books held by the West Yorkshire Archive Service show he also owned and rented out more than twenty smaller properties at Burley Place.6

He also continued to be active in civic politics. In 1846, Leeds got its first town council, and Ardill stood unsuccessfully as a Chartist candidate. By 1852, however, he had thrown in his lot with the Liberals, and was duly elected. He would continue in office until his death on 4 June 1869. One of his final interventions in local politics was to raise doubts about the need for a new town cemetery.

John Ardill was buried at St Michael and All Angels, Headingley. He shares the grave with his mother in law, Dorothy Pearson, and wife Jane, who survived him by nearly four decades.

Sources

1. Baptisms in the Parish of Addingham, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1512-1812.

2. ‘John Ardill and His Traducers’, Manchester Examiner, 6 November 1847, p6.

3. Leeds Times, 2 September 1837, p1.

4. West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1813-1935

5. Chartist Songs, And Other Pieces, by William Hick (Leeds, 1840). Full text on Google Books, accessed 2 December 2023.

6. West Yorkshire, England, Select Rate Books, Accounts and Censuses, 1705–1893, via Ancestry. Accessed 10 December 2023.

All newspapers referenced in this article were accessed by the British Newspaper Archive. Entries for NS refer to the Northern Star.