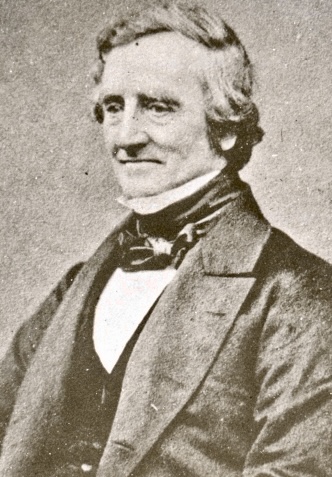

James Watson, 1799 – 1874

James Watson was one of the quartet of radical London publishers who were at the heart of the battle of the unstamped press and later went on to form the London Working Men’s Association. Influenced by Robert Owen and Richard Carlile, Watson was also a leading advocate of co-operative ideas and free-thought.

Born at Malton, a town on the road north from York to Whitby on 21 September 1799, Watson lost his father while still less than a year old.

His mother, a Sunday school teacher in service to a local clergyman, taught him to read and write, and at the age of twelve, James was apprenticed to his mother’s employer ‘to learn field labour, work in the garden, clean horses, milk cows, and wait at table; occupations not very favourable to mental development’. After six years, however, the clergyman’s wife died and he left the town, cancelling Watson’s indenture.

At eighteen, Watson moved to Leeds in search of relatives and work. As he later recalled: ‘It was in the autumn of 1818 that I first became acquainted with politics and theology. Passing along Briggate one evening, I saw of the corner of Union Court a bill, which stated that the Radical Reformers held their meetings in a room in that court. Curiosity prompted me to go and hear what was going on. I found them reading Wooler’s Black Dwarf, Carlile’s Republican, and Cobbett’s Register. I remembered my mother being in the habit of reading Cobbett’s Register, and saying she wondered people spoke so much against it; she saw nothing bad in it, but she saw a great many good things in it. After hearing it read in the meeting room, I was of my mother’s opinion.’

For the next four years, with friends found from among the city’s radical reformers, Watson spread ‘liberal and free-thinking literature’ and ideas at public meetings in the town. Then, in 1822, the leading free-thinker, Richard Carlile, sent word asking for volunteers to work in his shop while he himself served a gaol sentence for blasphemy in Dorchester Prison – and Watson set off for London.

At the end of February 1823, while working at Carlile’s shop at 201 Strand, Watson was arrested for ‘maliciously’ selling a copy of Elihu Palmer’s blasphemous Principles of Nature to a police agent, and he was imprisoned at Coldbath Fields for a year. After being released on 24 April, 1824, Watson found paid work hard to get, until Carlile invited him to take over the management of his business.

When Carlile too was released, at the end of 1825, Watson was found a place with the publisher of the Republican, learning ‘the art of a compositor’. He survived cholera, and was put to work composing ‘two volumes, one in Greek, the other in Greek and English’, which kept him in work for the next eighteen months. During this period of his life, he also came under the influence of Robert Owen’s ideas. As he later recalled: ‘In April, 1828, I undertook the agency of the Co-operative Store at 36, Red Lion Square, and I remained in that employment until Christmas, 1829.’

In early 1830, Watson set off on a tour of Yorkshire towns, advocating the establishment of co-operative societies, before returning to London, where at 33, Windmill Street, Finsbury, Square, he set up in business as a bookseller. He soon became a printer and publisher too, and in 1831 he joined the National Union of the Working Classes.

Watson now came into regular contact with the city’s leading radical publishers – William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, and John Cleave – and others, including William Benbow, who would go on to form the core of the London Working Men’s Association.

But there were other battles to fight first. Watson later wrote: ‘In 1832 the excitement of the people on the subject of the Reform Bill was at its height. The cholera being very bad all over the country, the Government, to please the Agnewites, ordered a “general fast”. The members of the National Union, to mark their contempt for such an order, determined to have a procession through the streets of London, and afterwards to have a general feast. In April I was arrested, with Messrs. Lovett and Benbow, for advising and leading the procession. We were liberated on bail, tried on the 16th of May, each conducting his own defence, and all acquitted.’

There was also a war of the unstamped press to win. Towards the end of 1832, Hetherington was sent to Clerkenwell Prison for publishing the Poor Man’s Guardian, swiftly joined by Watson for the crime of selling the paper. In 1834, however, Watson was able to significantly expand his publishing business thanks to a 450 guinea legacy left to him by a friend. All of this and £500 more was soon used up printing radical works which he sold for a shilling or less each.

That same year, as a member of the London Dorchester Committee, Watson was among the organisers of the great trade union meeting at Copenhagen Fields (now Caledonian Park in Islington) in support of the Dorchester labourers. On 3 June, he married Eleanor Byerley at St Luke’s, Finsbury, and less than two months later, after returning from honeymoon in Jersey, was sent back to prison for selling Hetherington’s ironically titled Conservative.

Watson was a founder member of the London Working Men’s Association in 1836, and actively sold copies of the People’s Charter when it finally appeared in print two years later. Like many in the LWMA, however, Watson recoiled from the politics of more radical Chartists, and played little active part in the movement. Despite this, he remained committed to the principles of the Charter and continued his involvement in other London radical causes.

James and Eleanor Watson eventually retired to Norwood. Here he died at his home in Hamilton Road on 29 November 1874. Watson was buried at Norwood Cemetery, where a grey granite obelisk was erected by friends to commemorate his ‘brave efforts to secure the rights of free speech’. The memorial is pictured right, although it is not clear whether this is the full obelisk erected after Watson’s death.

An entry in the Dictionary of National Biography concludes of Watson: ‘A frugal, severe, and self-denying liver, a thin, haggard, thoughtful man, with an intellectual face and a grave yet gentle manner, Watson was an uncommon type of English tradesman. He lost considerably over his publishing, his object being profitable reading for uneducated people rather than personal gain. At the same time he cared for the correctness and decent appearance of his books, even the cheapest. ”They were his children, he had none other.” An unstamped and absolutely free press became the practical object of his later years.’

Sources

James Watson: A Memoire of The Days of the Fight for a Free Press in England and of the Agitation for the People’s Charter, by W. J. Linton (1879). Available on the Minor Victorian Writers website. Accessed 19 November 2023.

‘Watson, James (1799-1874)’, by Thomas Seccombe, Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Vol 60 (1866-1923). Available via Wikisource. Accessed 19 November 2023.