Helen Macfarlane 1818 – 1860

Helen Macfarlane is now known to have been the first translator of the Communist Manifesto into English. But for a century or more, her involvement with the Chartist press was unknown, and her achievement unrecognised.

Few knew her identity at the time, and fewer still remembered her in the years that followed, but Helen Macfarlane was probably the most influential woman who ever passed through the Chartist movement.

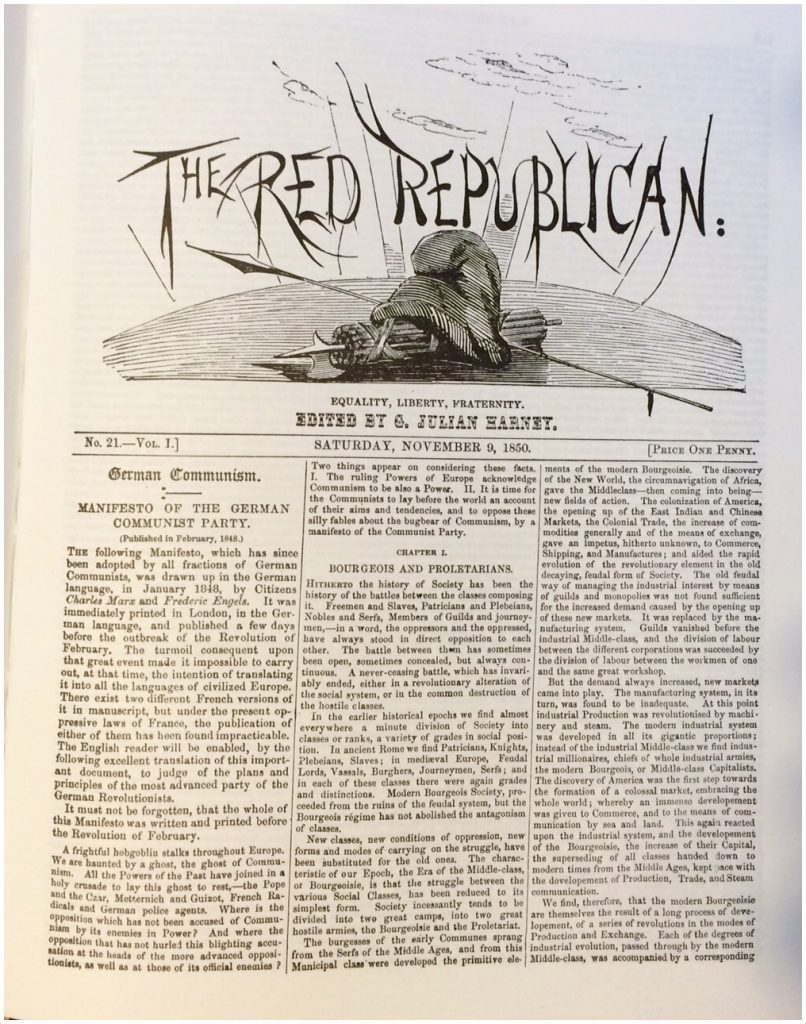

Writing under the name Howard Morton, Macfarlane made the first English translation of the Communist Manifesto, which appeared in George Julian Harney’s Red Republican in 1850, and was described by Karl Marx as “the only collaborator on his spouting rag who had original ideas”. Over the course of a year she contributed a series of articles to Harney’s publication which drew on German philosophy and theological sources. But after that, she is known to have written nothing further for publication anywhere.

Indeed, Macfarlane disappeared from politics after breaking with Harney in 1851 and was all but forgotten until her identity was tentatively revealed by Harney’s biographer A.R. Schoyen in 1958. But even then and ever since, her early life and what happened to her subsequently have been a mystery.

Then, in late 2012, the mystery was solved by her biographer David Black and BBC Radio Scotland researcher and broadcaster Louise Yeoman. Their findings were broadcast in BBC Radio Scotland’s Women With a Past series (now no longer available on the BBC website, unfortunately).

Born on 25 September 1818 in Scotland, Macfarlane was the youngest of 11 children. Her father George, the descendant of minor Scottish lairds, owned a calico-printing works at Barrhead, and her mother, Helen Stenhouse, came from a similarly well-off family of calico printers. Macfarlane’s early childhood must have been comfortable, but the family found itself destitute when mechanisation forced the business to the wall in 1842.

In the year of revolutions of 1848, probably while working as a governess, she witnessed the Vienna uprising against the Hapsburg monarchy, before returning to Britain where she began to contribute articles for Harney and came to know Marx and Friedrich Engels.

Today, Macfarlane’s translation of Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto, first published in German some two years earlier, is remembered chiefly for its opening phrase: ‘A frightful hobgoblin stalks throughout Europe. We are haunted by a ghost, the ghost of Communism.’ Though unfamiliar to modern readers more used to the later ‘A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of communism’, the word ‘hobgoblin’ would have been familiar to Chartists as it had previously been used by Feargus O’Connor in similar circumstances. Macfarlane also chose to offer readers options where direct translations were difficult – for example, offering four different English words for the German ‘gespenst’ in the Manifesto’s opening paragraph.

But Macfarlane’s involvement with Chartism and the radical London milieu in which Harney, Marx and Engels moved was shortlived. In 1851, after a disastrous New Year’s Eve party, Macfarlane broke with Harney and left Chartism and its connections behind. According to letter Marx sent to Engels a short time later, this was because Harney’s wife Mary Cameron, herself from a radical working-class family of weavers in Scotland, had insulted her. The truth, and the cause of the dispute, will never be known.

However, in 1852 Helen Macfarlane married Francis Proust, himself a former radical exile, and the couple sailed for South Africa to join Macfarlane’s brothers. Tragically, there was to be no new life together – Francis died even before the ship left British waters, and her only child soon after their arrival.

After returning to England in 1854, Helen met a Church of England vicar, John Wilkinson Edwards, himself widowed with 11 children and in 1856 at Chorlton in Lancashire they married. Macfarlane (or Proust, the surname under which she married) became a vicar’s wife, at St. Michael’s Church, Baddiley, just outside Nantwich. The couple had two sons, Herbert and Walter. But in 1860, at the age of only 41, Helen became ill with bronchitis and died. She is buried in the churchyard of St. Michael’s.

The inscription on the gravestone reads: “Sacred to the memory of Helen, wife of the Rev. John W Edwards, who fell asleep in Jesus, March the 29th 1860, aged 41 years. So he giveth his beloved sleep.”

Notes and sources

Red Antigone: The Life and World of Helen Macfarlane: Portrait of a Chartist Journalist, Feminist Revolutionary and Translator of the Communist Manifesto, by David Black (BPC Publishers, 2024).

Red Chartist: Helen Macfarlane 1818-60 The Complete Annotated Writings and her Translation Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto, by David Black (BPC Publishers, 2024).

The Chartist Challenge, by A.R. Schoyen (Heinemann, 1958).

Helen Macfarlane was the subject of two papers at Chartism Day 2024. David Black spoke about her life and work, while Sam Miller discussed her translation of the Communist Manifesto, reported here on the Society for the Study of Labour History website.