Elland Female Radical Association

The West Riding of Yorkshire was a Chartist stronghold from the movement’s earliest days. But Chartist organisation did not emerge from a vacuum: the women who formed the backbone of Elland’s Female Radical Association were veterans of the fight against the New Poor Law. This is their story.

The Female Radical Association at Elland, midway between Huddersfield and Halifax, certainly pre-dates the publication of the People’s Charter by some months, and it may even have been formed at the same time as the men’s association as early as March 1837. In common with other such radical bodies in the West Riding and Lancashire weaving towns, the Elland women focused their efforts on opposition to the roll-out of the hated New Poor Law with its punitive workhouse system. This was a cause that affected many in a very direct way, and anger over this and the Whig government’s failure to address employer abuses in the factory system were among the key factors that by late 1838 had convinced millions of the need for a programme of political reform based on the Charter that would place power in the hands of the people.

Elland’s female radical association was active by February 1838, when it met to agree a petition to the Queen on the ‘unmercifully oppressive and tyrannical’ Act and to call for its repeal (Northern Star, 17 February 1838 p8). But while such sentiments were common, and other female radical associations were adopting similar petitions, the women of Elland were soon presented with a more direct opportunity to make their views very clear to the men attempting to implement the legislation.

Towards the end of February, women ‘mustered in strong numbers’ outside a meeting of the local poor law commissioners taking place at Elland workhouse, and ‘on the return of some of the gentle [poor law] guardians from the meeting, some of the females treat them with a roll in the snow; and one of them a stout portly man offered to treat them with a gill of ale each, if they would allow him to escape; but the bribe would not do’ (NS, 3 March 1838, p5).

Although it is not clear how many members and supporters the Female Radical Association could call on, the group must have been of some size to do this. When it held a public meeting some weeks later on 19 March, twenty-nine members signed up and paid their entrance money (NS, 24 March 1838, p 5). Leadership of the association, however, appears to have been in the hands of three women, only one of whom may have been native to the town.

Leaders of the association

Susannah Fearnley (sometimes Farnley). Born around 1800 in Northowram, a few miles north of Elland, Susey Scott married Caleb Pearson, a labourer, on 15 June 1823 at the parish church in Halifax; while he signed his name in the parish register, she made her mark. They had two sons: Dan, born 1824; and Thomas, born 1826. After Caleb’s death, Susey remarried on 1 February 1835; once again, she made her mark. Her new husband, Azariah Fearnley, was some ten years older than Susannah, born in Northowram in 1790 and a nonconformist. In June 1837, Susannah’s son Thomas was also entered into the nonconformist register. The family must have moved to Elland soon after Azariah and Susannah married. By early 1838 she was sufficiently well-known and trusted in the community to be elected to chair the female radical association, but there is no record of her husband having been involved in the male association. There is no sign of the Fearnleys in the 1841 census, but by 1851 Susannah had returned to Northowram and was a widow once more. Listed as the head of the household, she gave her occupation as handloom weaver; her son Dan, Scottish-born daughter-in-law Ann, and one-year-old granddaughter Susannah lived with her at their home in Sladdin Row.

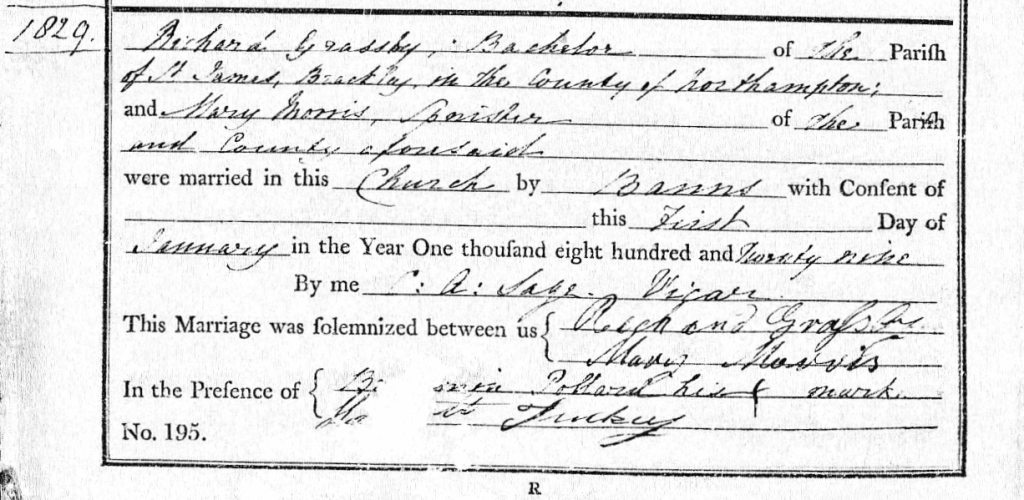

Mary Grassby (sometimes Grasby). Born in 1799 and baptised at Brackley in Northamptonshire, Mary was the daughter of John and Silence Morris (nee Maversly). She had a son, named William Wright Morris on 27 May 1827, who lived just a few weeks. The boy’s name appears to be a fairly clear indication of the father’s identity, though Mary is listed as a spinster in her son’s parish baptism record. Two years later, on 1 January 1829, Mary married Richard Grassby and the couple moved to Richard’s native Yorkshire. Together they had six children: John, born 1829; Rebecca, born 1830; Mary, born 1830 and died 1836; William, born 1834 and died 1835; Richard, born 1836; and notably Feargus Roger O’Connor in 1841. The family moved between Elland and Hull several times and Richard gave his occupation variously as mechanic, brickmaker and basket-maker. Of their six children, only Richard was born in Elland. In 1839, while they were living in Elland, Richard is regularly listed as an agent for the Northern Star; his younger brother James Grassby was also politically active in Hull before moving to London in the 1840s, where he was a leading member of the National Charter Association. Richard died in 1858, and the 1861 census has Mary as a basket-maker living with her eldest son John. She died in 1870.

Elizabeth Hanson. Elizabeth’s early life outside politics is the least well documented of the three. Later census returns suggest she was born around 1800 in Elland, although the most likely marriage record for her husband Abram (sometimes Abraham) Hanson is to an Elizabeth Fell of Wike, some 25 miles away, in February 1823. Abram (born 1798) was a shoe-maker, a largely self-educated working man who was prominent in Elland and served as both secretary and chair of Elland Radical Association, while Elizabeth was one of the triumvirate of women at the head of the town’s female radical association and is recorded as having spoken regularly at its meetings. The couple had seven children, including twins born in 1829, one of whom died in infancy. Those who made it to adulthood were: Sarah, born 1829; Frances, born 1831; Mary, born 1835; Emily, born 1836; Feargus, born 1839; and Elizabeth, born 1843. Abram appears to have died at some point in the 1850s, as the 1861 census records Elizabeth as the widowed head of her household in West Gate, Elland. Although there is no obvious record of her death, Elizabeth probably died some time before the 1871 census.

Arguments against the New Poor Law

The first recorded meeting of the Elland women took place at the Radical Association Room in the town on Monday 12 February 1838, though they may well have met earlier than this without sending reports to the Northern Star. The aim of the meeting was to call for repeal of the Poor Law Amendment Act through an address to the Queen, whose coronation was due to take place that June.

At the start of the meeting, Susannah Fearnley was voted into the chair and in her opening remarks set a tone for the new group’s activities ‘by exhorting the females present to take their affairs into their own hands, and not to rely on the exertions of others, least of all, on the House of Commons; but, at once to assert the dignity and equality of the sex, and, as the chief magistrate in the ream was now a female, to approach her respectfully and lay their grievances before her; and should their application be unsuccessful, she would then call upon them to resist the enforcement of this cruel law even unto the death.’ There were loud cheers.

Mary Grassby (Grasby in the report) moved a resolution, ‘That this meeting considers the New Poor Law Amendment Act an infringement on our rights. Because it considers it to be unmercifully oppressive and tyrannical, sparking neither sex nor age. Because it takes all power out of the hands of those who pay and who have the best right of knowledge and means of disposing of the rates. Because it places the sole power in the hands of the three Commissioners who are utter strangers to the circumstances of the poor. We therefore as part of the community consider it a duty incumbent upon us to come forward in heart and mind, to solicit its total repeal.’

She told the meeting that the law ‘was not concocted by men but by fiends in the shape of men’. It had, she said, ‘been hatched and bred in the bottomless pit’. To cheers, she denounced the Act as a ‘most unchristian law’. As the Northern Star reported: ‘They might be asked why women should interfere in public matters. She would answer at once, it was a woman’s duty to be there; for women had more to fear from this bill than men. (Cheers.)’

Seconding the resolution, Elizabeth Hanson said that ‘she knew of families who had not one penny a day, per head, to live on. Thus, then, they were preparing them for the Bastile diet before they put them in. Mrs H. then read, and commented on a Poor Law dietary table, observing, that food like this was calculated not to do them good, but to hasten them into eternity, and prepare subjects for the dissecting knife.’

The women had good reason to fear the new regime. A parliamentary report of 1834 put the workhouse population for Elland cum Greetland at thirty-four. Of these, twelve were under the age of 20, and the remainder all over the age of 50 (60 in the case of the men). Support for men and women of working age came in the form of outdoor relief, which enabled families to stay together in their own homes when wages were low and work scarce. The New Poor Law, which promised to abandon outdoor relief in favour of workhouse provision, threatened to uproot families and tear them apart.

The workhouse regime was especially degrading for women. According to the report, ‘Mrs H alluded to the personal disfiguration of the hair cutting off, which excited much disapprobation; this was followed by a description of the grogram gowns, of shoddy and paste, in which the inmates of the Bastiles are attired’. And she concluded her speech ‘amid the tears, cheers and execrations of the audience’. Not surprisingly, the address was agreed, and votes of thanks passed to all concerned.

A national story

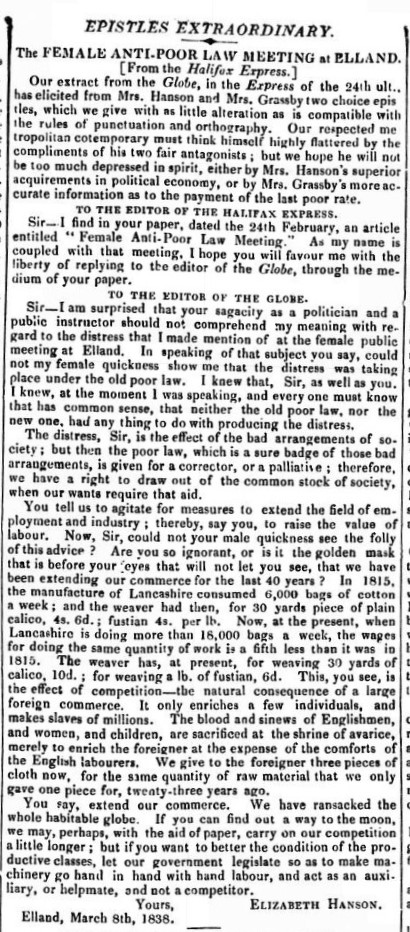

After the Northern Star’s report, the Globe, a London-based evening paper once but no longer considered radical, picked up the story, telling its readers sarcastically, ‘The crisis is come! The old-womanhood of the empire has risen, is rising, or is about to rise, as one old woman – and what do you think? Against the new Poor Law!’ (Globe, 20 February 1838, p2). Recounting Mary Grassby’s speech, it claimed its criticisms of the New Poor Law were ‘all because Mrs Grasby’s spouse, as we are led to infer, can’t pay his way and provide suitably for Mrs Grasby and the little Grasbys! Considering Mrs Grasby’s evident talent for scolding, it is clear to us that something besides the new Poor Law is what prevents her from “soothing the sorrows” of poor Mr Grasby. We confess we pity Grasby. Perhaps he has taken to drinking. Poor fellow!’ And so it went on.

The slurs would probably have gone unnoticed in Elland had the Halifax Express not lifted the Globe’s story in full and rerun it (Halifax Express, 24 February, 1838).

Understandably furious, both Elizabeth Hanson and Mary Grassby wrote back, Elizabeth to the editor of the Globe and Mary to the Halifax Express. Its slurs on her husband were clearly more damaging locally than they would have been in London. The Globe ran the full text of both letters, billing their correspondence condescendingly as ‘two choice epistles, which we give with as little alteration as is compatible with the rules of punctuation and orthography’ (Globe, 22 March, 1838, p3). It did, however, run them in full.

Elizabeth Hanson condescended back at the Globe’s editor in equal measure. ‘I am surprised that your sagacity as a politician and a public instructor should not comprehend my meaning with regard to the distress that I made mention of at a female public meeting at Elland,’ she began. ‘In speaking of that subject, you say, could not my female quickness show me that the distress was taking place under the old poor law. I knew that, Sir, as well as you. I knew, at the moment I was speaking, and every one must know that has common sense, that neither the old poor law nor the new one, had any thing to do with producing the distress.’ Rather, she pointed out, the distress was the effect of ‘the bad arrangements of society’.

She then took the paper’s editor to task for his advice that they should agitate to ‘extend the field of employment and industry’ to raise wages. ‘Now Sir,’ she continued, ‘could not your male quickness see the folly of this advice?’ After a huge expansion of commerce over the previous forty years, she pointed out, weavers now earned less than they had in 1815. Competition had simply enriched a few individuals and made slaves of millions. ‘You say, extend our commerce. We have ransacked the whole habitable globe. If you can find out a way to the moon, we may, perhaps, with the aid of paper, carry on our competition a little longer; but if you want to better the condition of the productive classes, let our government legislate so as to make machinery go hand in hand with hand labour, and act as an auxiliary, or helpmeet, and not competitor’.

Mary Grassby’s letter was a more personal response to the Globe’s ‘declamation and personal attacks’ parroted by the Halifax Express. She addressed its allegation that her family lived at the expense of the ratepayer, pointing out: ‘Now, Sir, I look upon such an assertion as this with the utmost contempt; for instead of living upon the rates, we have always been a paymaster to the poor, and I am proud to assert that we are not one rate behind.’ Concluding with an appeal to scripture on the judgement awaiting those who turned away the poor, she signed off, ‘I remain, yours unhurt by calumny.’

Confronted with an unexpectedly cogent argument, the editor of the Globe returned to the fray with a series of liberal free-market arguments that would still be familiar today on the need to keep poor relief low so as to encourage the feckless to work and to expand commerce to create jobs (Globe, 27 March 1838, p4).

The Elland female radicals may never have seen this final salvo on the part of the Globe. It did at least acknowledge the substance of their arguments, albeit in a way that enabled the paper to reassure its readers of its own rightness. But it seems unlikely that a spat with the editor of a London newspaper would have greatly exercised them. Both Elizabeth Hanson and Mary Grassby had young families to raise, and Elizabeth would soon become pregnant again with the son she and Abram would name after Feargus O’Connor.

Despite the women’s efforts, the New Poor Law was implemented in Elland and elsewhere. The Halifax Poor Law Union, established in 1837 and covering nineteen parishes including Elland, bought land in Halifax on which to build a new central workhouse. When it opened in 1840, paupers from across the district were moved in and the older buildings closed.

But this was not the end of the story for Elland’s female radicals. After publication of the People’s Charter in 1838, and like many pre-existing male radical societies, the Elland FRA swiftly evolved into a Chartist body. A report of the West Riding Delegate Meeting held on 18 January the following year passed a resolution thanking the female radicals of Elland for their ‘liberal donation’ to the proposed National Convention (NS, 2 February 1839, p8). They were not, however, represented at the delegate meeting – or at the Convention.

Notes and sources

Dorothy Thompson included a chapter titled ‘The Women’ in The Chartists: Popular Politics in the Industrial Revolution (first published by Maurice Temple Smith, 1984; republished by Breviary Stuff Publications, 2013) which discusses the Elland Female Radical Association and other groups.

There is an excellent account of Abram and Elizabeth’s Hanson’s part in radical politics and Chartism in Elland in Malcolm Chase’s Chartism: A New History (Manchester University Press, 2007).

Information on poor relief in Elland and the creation of the Halifax Poor Law Union comes from Peter Higginbotham’s invaluable The Workhouse website. Its page on Halifax can be found here.

All newspaper reports cited above are from papers in the British Newspaper Archive. References to the Northern Star are given as NS after the first mention.

Records of births, baptisms, marriages and deaths, along with census records and other personal information are to be found on Ancestry UK and/or FindMyPast.

Read more about Women in Chartism and Women Chartists.