Chartism and the Anti Corn Law League

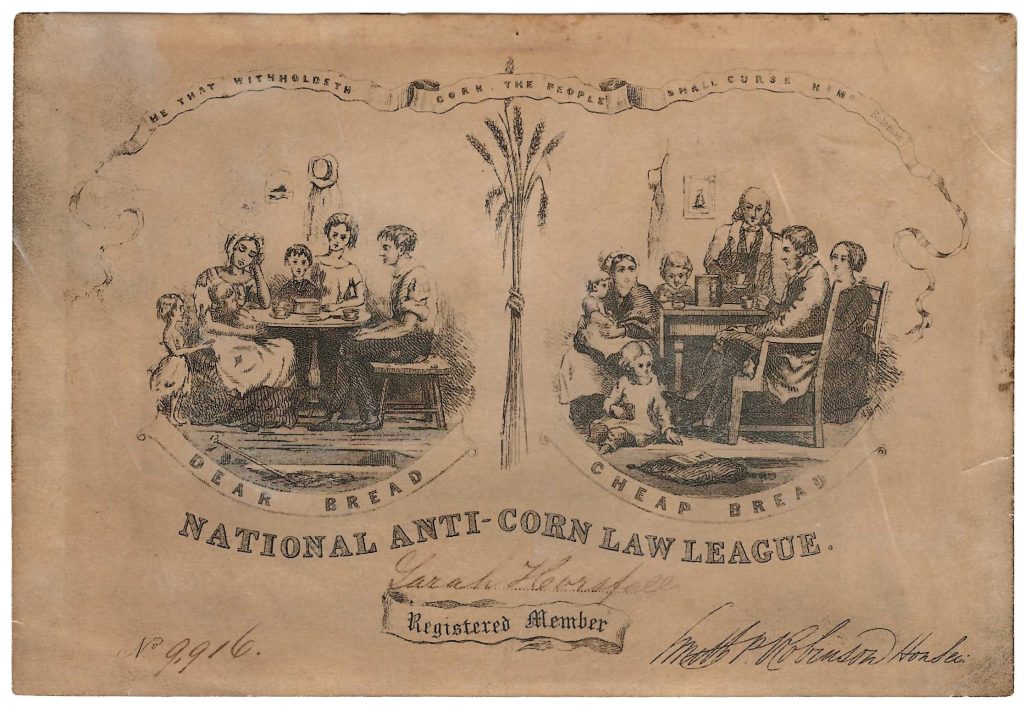

The Chartist movement existed in an uneasy relationship with the campaign against the corn laws.

Introduced in 1804 and intended to protect landowners by imposing a duty on imported grain, the corn laws had the effect of keeping the price of bread at artificially high levels. Manufacturers who objected to having to pay high wages so that their employees could eat, and workers themselves, were resentful of this subsidy to farmers.

Trade depression in the late 1830s and a run of bad harvests brought this resentment to the boil and in March 1839 the Manchester businessman Richard Cobden took the lead in uniting separate anti corn law associations in London and Lancashire into a single Anti Corn Law League.

Under the influence of Cobden’s leadership and John Bright’s oratory, thousands flocked to the cause – among them many middle class radicals and industrialists.

Many Chartists did support the Anti Corn Law League. Some middle-class backers of Chartism – notably the serial supporter of good causes Joseph Sturge – kept a foot in both camps. The movement also drew support from factory workers in Manchester, Huddersfield and, most notably Sheffield, where Ebenezer Elliott, known as the Corn Law Rhymer for his anti-corn law poems, was prominent early on in both causes. In their book The People’s Bread: a history of the Anti Corn Law League, Paul A Pickering and Alex Tyrrell mention many others.

In Bath, the Chartist lecturer Henry Vincent organised a union between corn-law repealers and Chartists. In Preston and at Newchurch, Chartists supported the Anti Corn Law League case. And when Exeter Chartist Association collapsed, its secretary offered to help the League instead. At Tiverton, the secretary of the local Chartists told a debater sent by the Anti Corn Law League that his members were willing to break up the meeting if called on to do so.

The Anti Corn Law League put considerable effort into winning and keeping the support of Chartist sympathisers, arguing that it was “a great error” to think that by campaigning for a repeal of the corn laws they needed to relax their efforts to win the vote, and indeed that, without repeal of the corn laws, an extension of the right to vote would be impossible.

But working class radicals who remembered middle-class entreaties to support the 1832 Reform Act, only to be left outside the political system and without the vote once those same middle class reformers had won the franchise for themselves, were naturally suspicious.

Their suspicions would only have been confirmed by the Anti Corn Law League’s management of one its most successful initiatives, a conference of 644 members of the clergy called to pass resolutions condemning the corn laws on moral and religious grounds. Though the “convocation” consisted almost entirely of independents and clergy from relatively minor dissenting sects, Arthur O’Neill and other preachers of the Christian Chartist Church along with three “Rational Religionists” were excluded from the event. And William Hill, editor of the Chartist Northern Star, who attended as a Swedenborgian minister, was denied permission to speak on the causes of social hardship.

As with all other causes considered to be a distraction from the Charter, the campaign against the corn laws was also vigorously denounced by Feargus O’Connor, who was quick to point out that the League was essentially an employers’ organisation. In fact, when the general strike of 1842 broke out while delegates to a National Charter Association conference were gathering in Manchester, O’Connor’s first reaction was to distance himself and Chartism from the strike because of its links to anti corn law agitation.

The Anti Corn Law League succeeded in its campaign in 1846. It did so in part because the circumstances of the potato famine in Ireland swayed prime minister Robert Peel to the view that the taxes on corn could not be sustained, in part because it achieved what Chartism managed only later and less successfully in winning the election of Cobbett and a number of other supporters to Parliament, and in large part because the now powerful industrialists were no longer prepared to subsidise the vestiges of a feudal economy.

The Anti Corn Law League was also better funded, better equipped, more highly centralised and much more professional than the National Charter Association could ever hope to be. Alexander Somerville, a journalist secretly in the pay of Cobden, described a visit to Newall’s Buildings, the Manchester head office of the league, in 1843. This account is taken from his book The Whistler at the Plough, first published in 1852 and reprinted by The Merlin Press in 1989.

Inside the offices of the Anti Corn Law League

“Accordingly at ten o’clock I was in Market Street , a principal thoroughfare in Manchester . A wide open stairway, with shops on each side of its entrance, rises from the level of the pavement, and lands on the first floor of a very extensive house called ‘Newall’s Buildings’. The house consists of four floors, all of which are occupied by the League, save the basement. We must, therefore, ascend the stair, which is wide enough to admit four or five persons walking abreast.

“On reaching a spacious landing, or lobby, we turn to the left, and, entering by a door, see a counter somewhere between forty and fifty feet in length, behind which several men and boys are busily employed, some registering letters in books, some keeping accounts, some folding and addressing newspapers, others going out with messages and parcels. This is the general office, and the number of persons here employed is, at the present time, ten. Beyond this is the Council Room, which, for the present, we shall leave behind and go up stairs to the second floor.Here we have a large room, probably forty feet by thirty, with a table in the centre running lengthwise, with seats around for a number of persons, who meet in the evenings, and who are called the ‘Manchester Committee’.”He goes on: “During the day this room is occupied by those who keep the account of cards issued and returned to and from all parts of the kingdom. A professional accountant is retained for this department, and a committee of members of council give him directions and inspect his books. These books are said to be very ingeniously arranged, so as to shew at a glance the value of the cards sent out, their value being represented by certain alphabetical letters and numbers, the names and residences of the parties to whom sent, the amounts of deficiencies of those returned and so on. Passing from this room we come to another, from which all the correspondence is issued. From this office letters to the amount of several thousands a-day go forth to all parts of the kingdom. While here, I saw letters addressed to all the foreign ambassadors, and all the mayors and provosts of corporate towns of the United Kingdom, inviting them to the great banquet which is to be given in the last week of this month … In this office copies of all the parliamentary registries of the kingdom are kept, so that any elector’s name and residence is at once found, and, if necessary, such elector is communicated with by letter or parcel of tracts, irrespective of the committees in his own district.Passing from this apartment, we see two or three small rooms, in which various committees of members of the council meet. Some of these committees are permanent, some temporary. Of those which are permanent I may name that for receiving all applications for lecturers and deputations to public meetings. … In another large room on this floor is the packing department. Here several men are at work making up bales of tracts, each weighing upwards of a hundred weight, and despatching them to all parts of the kingdom for distribution among the electors. From sixty to seventy of these bales are sent off in a week, that is, from three to three and a-half tons of arguments against the Corn Laws!”

Finally: “Leaving this and going to the floor above, we find a great number of printers, presses, folders, stitchers, and others connected with printing, at work. But in addition to the printing and issuing of tracts here, the League has several other printers at work in this and other towns of the Kingdom. Altogether they have twelve master-printers employed, one of whom, in Manchester , pays upwards of £100 a week in wages for League work alone.”

Organisation and finances

Some idea of the wealth of the Anti Corn Law League can also be seen in the annual accounts, which can still be seen in the Cobden Collection at West Sussex Records Office .

At the beginning of the 15-month period from 9 September 1843, the Anti Corn Law League had cash in hand of £2,476, 10s, 3d. By 31 December 1844, it had raised £82,735, 3s, 5d from subscriptions and a further £797, 13s, 7d in bank interest. In the following year subscriptions alone brought in a further £35,678, 8s, 10d, and from January to October 1846 when the organisation was wound up they generated a further £41,897 12s 7d.

A second document in the Cobden Collection provides a breakdown of the largest donations – though, unfortunately, without naming the donors. It includes 889 subscriptions of £10 or more each, of which 10 (all from Lancashire) were of £1,000 each, while 20 more (11 from Lancashire, 5 from Yorkshire, 2 from London and 2 from elsewhere) were each of £500.

By contrast, though the Chartist National Land Company initiative raised more than £100,000 to buy smallholdings, it took 70,000 small donations to raise this sum, and when Ernest Jones effectively took personal control of the National Charter Association in 1851, the remaining members of the executive struggled for six months to pay off the organisation’s debts of less than £40.

The money raised by the Anti Corn Law League was spent on projects that would be reasonably standard for a campaign group today. In the 15 months to 31 December 1844, it spent

- £7,102, 16s, 8d on registration and tract distribution, including expenses in registration courts, the wages of clerks, and travelling expenses on registration business;

- £4,103, 10s, 10d on grants to local free trade committees;

- £1,848, 9s, 11d on meetings expenses, including the hire of rooms, erecting hustings and all the expenses of public meetings;

- £11,344, 14s, 1d on the printing of stationery, newspapers, reporting and so on;

- £1,467, 12s, 9d on sundry office expenses, petty cash and incidental expenses including “repairs, alterations, coals, cleaning &c &c”;

- £1,640, 14s, 7d on the salaries of clerks and weekly wages;

- £19,786, 9s, 10d on the expenses of publishing League newspapers, including salaries for editors and contributors, stamps, paper and printing. The average circulation during that period, the accounts record, was 20,000 copies;

- £606 on furniture and fixtures;

- £2,645, 16s, 10d on deputation expenses, “including travelling expenses to attend meetings & Parliamentary Ekections in various parts of the United Kingdom ”.

- £3,652, 8s, 7d on salaries and expenses for lecturers;

- £424, 16s, 11d on legal expenses;

- £4,813, 15s, 6d on rent, taxes and gas including the rent of Covent Garden Theatre [where the League held a three-week Grand Bazaar featuring crafts and produce brought for sale by supporters from all over the country] and London offices; and

- £1,498, 15s, 0d on postage stamps, carriage and postage.

Although Somerville ‘s report suggests that the League employed considerably more people, the accounts name 13 employees and record their salaries and expenses for the period (see box below).

The Anti Corn Law League appears to have been able to pay good salaries. Figures compiled in 1838 for Leeds by the Statistical Society and quoted by Eric Hobsbawm in Labouring Men (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1968) show weekly wages for millwrights of 26 shillings, gunsmiths 25 shillings, shoemakers 14 shillings and weavers 13 shillings. Even then, shoemakers and weavers could expect on average to work just 10 months of the year, cutting their annual incomes still further.

Employees of the Anti Corn Law League

| Name | Salary 1844 | Expenses 1844 | Salary 1845 |

|---|---|---|---|

| W H James | 150 | £171, 6s 9d | 300 |

| Thomas Plint | £303, 10s 10d | £224, 10s, 10d | 350 |

| Joseph Jones | 107 | £217, 0s, 6d | 156 |

| John Murray | 100 | £281, 0s, 2d | 100 |

| T Falvey | £124, 3s, 4d | £351, 2s, 4d | £170, 5s, 0d |

| J J Finnigan | 80 | £121, 19s, 9d | 80 |

| James Moorhouse | £157, 5s, 0d | £522, 9s, 5d | £163, 10s, 0d |

| Henry Lyons | £70, 16s, 8d | £24, 18s, 0d | 120 |

| D Liddell | 204 | £70, 10s, 7d | 204 |

| J F Bontems | — | — | 150 |

| George Huggett | 194 | £106, 2s, 0d | 134 |

| Sidney Smith | — | — | 350 |

| P Harwood | — | — | £41, 13s, 4d |

a . James was engaged for six months from 1 May to 31 October 1844; in addition to the expenses shown the accounts record “Middlesex Registration Society £485, 18s, 6d.

b. “T Plint in this year [1844] made a deduction for time employed in his own affairs, and also for £10 paid him by the Leeds Committee.”

c. Jones’ salary was for eight months of 1844, from 1 May onwards.

d. Lyons’ salary was from mid April 1844 to the end of the year.

e. Huggett’s salary was for eigh months of 1844, from 1 May onwards.

f. Bontems’ salary was from 25 March to 31 December 1845.

g. Huggett’s salary was for 5.5 months of 1845.

h. Harwood’s salary was for 2 months of 1845.

John Murray, Timothy Falvey, John Finnigan and Sidney Smith were employed as league lecturers.

The free trade bazaar

One of the largest and most imaginative combined fundraising and publicity events organised by the Anti Corn Law League was a “free trade bazaar”, which it held over three weeks in May 1845.

The League booked the Covent Garden Theatre, and invited its supporters to take stands displaying and offering for sale handicrafts and products in support of the cause. From reports provided by the League itself, the response appears to have been enthusiastic, with items ranging from Scottish tartan cloths to Staffordshire pottery on sale and crowds flocking to see what looks to have been a modest precursor to the Great Exhibition of 1851.

During the event, the League published a series of 15 daily copies of the Bazaar Gazette , providing visitors with a souvenir and information on the products on show, leavened with a mix of free trade politics. This extract from the final issue gives a flavour of the event’s popularity.

“The Hall was open on Thursday until ten o’clock, and during the whole time was densely crowded. At nine o’clock in the evening the pressure was so great, that it was feared there would be a necessity for closing the doors. According to the best calculation that we have been able to make, about fifteen hundred can be conveniently admitted per hour, and about two thousand can be accommodated in the Bazaar at one time. As visitors generally average two hours in going round the whole exhibition, we doubt the possibility of admitting more than from eight to nine thousand per day, even if the Hall should be thronged during the whole period of the doors remaining open.”

Manchester Anti Corn Law Association Council, 1839-40

| Name | Age in 1840 | Born | Marital status | Children | Religion | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph Adshead | 40 | Ross, Hereford | M | — | Independent | Merchant, estate agent |

| Elkanah Armitage | 46 | Newton Heath, Manchester | M+ | 9 | Independent | Draper, manufacturer |

| Edmund Ashworth | 40 | Birtwistle, Bolton | M+ | 9 | Quaker | Manufacturer |

| Henry Ashworth | 46 | Birtwistle, Bolton | M+ | 11 | Quaker | Manufacturer |

| John Ballantyne | — | Scotland | — | — | — | Editor |

| Andrew Bannerman | — | Scotland | — | — | Dissenter | Calico printer, banker |

| James R Barnes | — | — | M | 1 | — | Cotton spinner, railway shares |

| William Besley | — | — | M+ | — | — | Agent |

| John Brewer | — | — | — | — | — | Packer |

| John Brooks | 56 | Whalley, Lancs | M+ | — | C of E | Manufacturer, merchant |

| Robert Bunting | — | — | — | — | — | Baker, flour dealer |

| Thomas Burgess | — | — | — | — | — | Calico dealer |

| William R Callender | 46 | Birmingham | M+ | 2 | Independent | Manufacturer, merchant |

| James Carlton | — | — | — | — | Independent | Manufacturer, merchant |

| James Chadwick | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| James Chapman | — | — | — | — | — | Solicitor |

| Walter Clark | — | — | — | — | — | Commission agent |

| Richard Cobden | 36 | Dunford, Essex | M+ | 1 | C of E | Manufacturer |

| Matthew Curtis | 33 | Manchester | M | 4 | C of E | Engineer, machine maker |

| Samuel D Darbishire | 44 | — | M+ | — | Unitarian | Solicitor, railway shares |

| George Dixon | — | — | — | — | — | Woollen manufacturer |

| Joseph C Dyer | 60 | Conn. USA | M | 2 | — | Manufacturer, banking |

| Peter Eckersley | — | — | M | 1 | Unitarian | Linen draper |

| James Edwards | — | — | — | — | Independent | Flour dealer |

| Edward Evans | — | — | M+ | — | — | Merchant, railway shares |

| Richard T Evans | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| William Evans | — | — | M+ | 1 | — | Drysalter, railway shares |

| James G Frost | died 1840 | — | — | — | — | Corn merchant |

| John H Fuller | — | — | — | — | — | Estate agent |

| Jeremiah Garnett | 47 | Wharfeside, Otley | M+ | 4 | C of E | Estate agent, journalist |

| William Goodier | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Joseph F Grafton | — | — | M | 1 | Independent | Calico printer |

| Rober H Greg | 45 | Manchester | M+ | 6 | Unitarian | Cotton manufacturer |

| Henry H Grounds | — | — | — | — | — | Merchant, railway shares |

| George Hadfield | 52 | Sheffield | M+ | — | Independent | Solicitor |

| Edward Hall | — | — | M+ | — | — | Manufacturer |

| James Hampson | — | — | — | — | — | Grocer, wholesale provision dealer |

| Thomas Harbottle | — | — | M+ | — | Independent | Cotton spinner, manufacturer |

| William Harvey | 57 | Whittington, Derbyshire | M | 5 | Bible Christian | Cotton spinner |

| Alexander Henry | 62 | Ireland, raised USA | M | 2 | Unitarian | Merchant, railway shares |

| Joseph Heron | 31 | Manchester | M (aged 71) | — | Independent | Solicitor |

| John Higson | — | — | — | — | — | Solicitor |

| Thomas Higson | 36 | Manchester | M+ | 4 | — | Solicitor |

| Robert Holland | — | — | — | — | — | Cotton merchant |

| Holland Hoole | 44 | Manchester | M+ | 9 | Wesleyan | Cotton spinner |

| Thomas Hopkins | 60 | — | — | — | — | Gentleman |

| James Howie | — | Scotland | M+ | — | — | Calico printer |

| Isaac Hudson | — | — | — | — | — | Ribbon manufacturer, hosier |

| James Hudson | — | — | — | — | — | Fustian manufacturer |

| John Hyde | — | — | — | — | — | Merchant |

| James Kershaw | 45 | Manchester | M+ | 3 | Independent | Calico printer, cotton merchant |

| William Labrey | 47 | — | — | — | Quaker | Tea dealer |

| William Lindon | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| William Lockett | 63 | Manchester | M+ | — | — | Silk mercer (retired) |

| Francis Lowe | — | — | — | — | — | Traveller |

| John McFarlane | — | — | — | — | — | Merchant |

| John Mallon | — | — | M | 2 | — | Linen draper |

| Henry Marsland | 47 | — | Single | — | Unitarian | Cotton spinner, merchant |

| Samuel Marsland | — | — | — | — | Unitarian | Cotton spinner |

| Henry McConnel | 39 | Manchester | — | — | Unitarian | Cotton spinner |

| Thomas Molineaux | — | — | M+ | — | — | Glass manufacturer |

| F C Morton | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| James Murray | — | — | — | — | — | Banker |

| Joseph Nadin jnr | — | — | — | — | — | Solicitor, theatre owner |

| John Naylor | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Robert Nicholson | 38 | Ardwick, Manchester | — | — | Unitarian | Merchant |

| William Nicholson | — | – | M+ | — | — | Drysalter |

| William Nield | 51 | Bowdon, Cheshire | M | 1 | Quaker, Baptist | Calico printer |

| Aaron Nodal | — | — | M | 1 | Quaker | Grocer |

| Philip Novelli | — | Piedmont, Italy | — | — | — | Merchant |

| John Ogden | — | — | — | — | — | Solicitor |

| John S Ormerod | — | — | M | 1 | — | Salesman |

| Benjamin Pearson | — | — | — | — | Quaker | Blanket manufacturer |

| Robert N Phillips | 25 | Manchester | M+ | — | Unitarian | Merchant, manufacturer |

| Thomas Potter | 65 | Tadcaster, Yorks | M+ | 2 | Unitarian | Manufacturer, merchant |

| Archibald Prentice | 48 | Scotland | M+ | 1 | Presbyterian | Printer, publisher |

| Henry Rawson | 21 | Nottingham | M | 1 | Unitarian | Stockbroker, newspaper owner, railways |

| Jonathon Rawson | — | — | M+ | 1 | — | Merchant, manufacturer, throstle spinner |

| William Rawson | c53 | Nth Nottingham | M+ | 2? | Unitarian | Gentleman, railway shares |

| John Robley | — | — | — | — | — | Importer, grocer, tea dealer |

| Lawrence Rostron | died 1853 | — | M+ | — | Quaker | Merchant, calico printer |

| James B Scott | — | — | — | — | — | Calico printer |

| Jonathon Shaw | — | — | — | — | — | Cotton merchant |

| Isaac Shimwell | — | — | — | — | Independent | Smallware dealer |

| John Shuttleworth | 54 | Manchester | — | — | Independent Quaker, Unitarian | Stamp distributor |

| Abraham Smith | — | — | — | — | — | Gentleman |

| John B Smith | 47 | Coventry | M+ | — | Unitarian | Merchant banker, railway shares |

| Stephen Smith | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Thomas Smith | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| John Standring | 35 | — | — | — | — | Manufacturer, chemist |

| Samuel Stocks | — | — | — | — | Wesleyan | Manufacturer, cotton spinner, bleacher |

| Robert Stuart | 49 | Manchester | Single | — | — | Cotton spinner, banking |

| John E Taylor | 49 | Illminster, Somerset | M+ | — | Unitarian | Printer, publisher |

| Charles Tysoe | — | — | — | — | Bible Christian | Cotton spinner, manufacturer |

| Henry Wadkin | — | — | M | 1 | Quaker | Sewing cotton manufacturer |

| Charles J S Walker | 52 | Manchester | — | — | — | Gentleman, coal |

| Absalom Watkin | 53 | London | M+ | 4 | Methodist, C of E | Cotton broker |

| William B Watkins | 51 | — | M | 2 | C of E | Drysalter, merchant |

| Samuel Watts | — | — | M | 1 | Independent | Merchant |

| John Whitlow | — | — | M+ | — | — | Laceman, railway shares |

| John Wilkinson | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Paul F Willert | 46 | Mecklenburg-Strelitz | M | 1 | — | Merchant |

| Thomas H Williams | — | — | M+ | — | — | Agent |

| George Wilson | 32 | Hathersage, Derbyshire | M+ | — | Sandemanian | Starch manufacturer, railways |

| William Woodcock | — | — | — | — | — | Cotton merchant |

RADICAL REFORMERS,

FELLOW CITIZENS,

THINK!-is it not a great error to conclude that

UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE

will be gained one single day sooner by withholding your aid from your fellow citizens in their efforts to procure a Repeal of the

CORN LAWS ?

THINK!-Is it not a great error to conclude that in assisting your fellow citizens to procure a Repeal of the

CORN LAWS ,

you need relax in your own efforts to obtain

UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE ?

The two questions are distinct. Each is enough for separate exertions.

UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE

is demanded, because those who are taxed should have a voice in electing Members to the House of Commons. And because the working man has interests of as great importance in good governmetn as any other man whatever.

The REPEAL of the CORN LAWS

is demanded: Because dear bread is an evil – cheap bread a good.

Because they shut out food when most needed.

Because they injure trade and commerce, throw out and keep out of work many thousands of industrious people.

Because, when many thousands are unemployed, or only half employed, and doomed to starvation, they undersell one another, and wages fall;-thus perpetual injury is done to the whole body of working people, men, women, and children.

Because, by refusing to take corn from foreign nations, we disable them from taking our manufactures, and thus to an amazing extent prevent the increase of employment, which alone can cause good wages to be obtained.

The REPEAL of the CORN LAWS

is a general question, including every class, sect, and condition of the whole people, and “What concerns ALL, should be matainined by ALL!”

SIGN THE PETITIONS FOR REPEAL OF THE CORN LAWS.

The Repeal of these Laws, which, if not Repealed, will, at no distant time, starve to death vast numbers of our industrious people.

The Repeal of these Laws, which, when they have produced the result, shall make the obtainment of the suffrage impossible – since a beggarly people never did and never will compel the government to grant any Reform whatever.

Every man in England should therefore join in the demand, should raise, and should continue to cry aloud,

REPEAL of THE CORN LAWS.

Persons favourable to the Repeal of the Corn Laws are requested to enrol themselves Members of the Association.

PETITIONS READY PREPARED, may be had on application at the Rooms of the Metropolitan Anti Corn Law Association, No. 154, Strand .

—————- Printed by T. Brettell, Rupert Street, Haymarket.

Source: a leaflet in the Cobbett Collection, West Sussex Records Office