‘A host of gawping idlers have been gratified with a spectacle’: Chartists on Queen Victoria’s coronation

‘Owing to a press of more important matters, we could not notice this ceremony last week,’ declared the Newcastle-based Northern Liberator. Admittedly, when it did find space to report the coronation of the young Queen Victoria in its issue of 7 July 1838, it did so at length and in reverential terms.

The radical paper’s ambivalence, at once dismissive and deferential, broadly summed up the attitude many Chartists adopted towards the monarchy in general. With the brief reigns of two underwhelming Hanovarian monarchs fresh in the memory, few looked to the coronation of the nineteen-year-old Victoria on 28 June that year as the dawn of new golden age; but fewer were prepared to argue for an end to monarchy. The London Democratic Association and handful of others may have done their best to kept the fires of republicanism burning, but the flame was a feeble one.

Radicals directed their ire instead towards the waste of public money and the insult to the starving poor that such empty royal ceremonial represented. In the end, Victoria’s coronation would cost the public purse £69,421 – around £6.2 million in today’s money. By comparison, her immediate predecessor, William IV, who detested ceremony and had tried unsuccessfully to do without a coronation, had spent £43,159 (£4 million), and the unpopular and profligate George IV before him had blown £238,000 (£21.1 million).

A month before Victoria’s coronation was to take place on 28 June, London’s radicals had called a public meeting at the Crown and Anchor, a favourite meeting place, to petition Parliament for the ceremony to be postponed. Henry Vincent, soon to gain fame as a leading Chartist speaker, argued, according to the Northern Star (26 May 1838) that, ‘In a country where there were millions of our fellow countrymen known to be in a miserable and destitute condition, it would be disgraceful in the government, and derogatory to the true dignity of a great nation, to mock the misery of the people and to augment their hardships by an extravagant expenditure of the public money on a ceremony conferring no honour or power on our youthful Queen, but merely indulging a taste for tawdry splendour.’

The vote was carried by a large majority, to the evident discomfort of the Westminster MP Sir Francis Burdett, who had done his best to avoid the meeting, had then been voted out of the chair when he arrived nearly two hours late, and was now expected to present the petition to Parliament. Once a leading radical voice and great friend to the O’Connor family, Burdett was by this time moving rapidly into the Tory camp, and would shortly forsake his London seat for the less challenging rural constituency of North Wiltshire.

The following week, the Star’s parliamentary report (2 June 1838) began: ‘After some twaddle about the Coronation came a great deal of talk about the Irish Poor Law Bill.’

The coronation came at a time when the Chartist movement itself existed only in embryo. Although the London Working Men’s Association had promised publication of its new People’s Charter ‘in a few weeks’ as far back as July 1837, by the time Glasgow’s radicals held a great public meeting on 21 May the following year to adopt the Birmingham Political Union’s latest petition, the document was still not yet in print. Only over that summer and into the autumn, as the LWMA and BPU despatched ‘missionary’ speakers around the country did Charter and petition come together to bring Chartism to life.

Even the word itself had not yet been coined: among its earliest appearances in print is the Leeds Intelligencer’s report on 22 September 1838 of a huge demonstration in Palace Yard, Westminster, the previous Monday which it dismissed as ‘a demonstration of weakness on the part of the noisy leaders of the new political sect calling themselves “Chartists”.’

But already that June things were stirring.

On coronation day itself, reported the Star (30 June), between eight and ten thousand radicals gathered on Calton Hill in Edinburgh. ‘It was the largest and most respectable meeting the Radicals have ever had. Resolutions condemnatory of the coronation were unanimously adopted, and also an admirable address…’ All this despite the Lord Provost’s refusal to consent to the meeting and the hostility of the Edinburgh papers. ‘The people are getting their eyes opened, and the triumph of Democracy is hastening forward. Come it will. No power can resist its approach,’ declared the Star’s correspondent.

And in Newcastle, an estimated seventy thousand assembled on Town Moor on coronation day to hear Feargus O’Connor outline the Chartist demands. The trades turned out for the event with their banners, there were bands to entertain the crowds, and roads were blocked by their vast numbers for two miles around. The Northern Star described it as ‘the most splendid display of the working classes ever witnessed in England’, and decried the authorities for sending in detachments of the 5th Dragoon Guards and the 52nd foot regiment who marched ‘close to the hustings with fixed bayonets’ in an attempt to intimidate the crowd.

There were many smaller not-the-coronation events around the country.

In Lancashire, ‘the Socialists of Oldham resolved not to join in any pompous procession, but to hold a Social Festival on that day, without intoxication, useless ceremony, or idle conversation. They removed the pews from the meeting room, decorated it with evergreens, flowers and hangings, and hung portraits on the walls of ‘the most eminently useful and philanthropic men of modern times’. Some two hundred men, women and children sat down to tea, and when the tables were removed, and the musicians took their place in the singing gallery, the company were entertained with ‘dances, songs, recitations, &c., &c.’ (NS, 7 July 1838).

The Radicals of Colne, meanwhile, ‘determined to have a display for sound political principles’ (NS, 7 July 1838). They formed a procession with banners, flags and bands, and ‘accompanied by a select party of singers, moved through the principal parts of the town, making a stand at the most public places, and singing two popular songs, concluding with three cheers for Universal Suffrage and three cheers for the people the producers of all wealth’. After holding a public meeting with speeches by three working men, the procession moved to the town and sang a Radical song in the market place, ‘and afterwards dispersed in a most orderly and peaceable manner, shewing an example worthy of being imitated by their superiors in circumstances.’

And in Glasgow, ‘a party of forty gentleman, to show their contempt of illuminations, and all the degraded foolery of coronations, invited that stern Republican, Dr John Taylor, to a public supper in the Black Boy tavern’. After a large number of toasts and a speech by Taylor, soon to be one of the more radical members of the first Chartist Convention, the company were entertained by songs, and ‘resolved themselves into a committee for the formation of a Republican Society, to which a number gave in their names, and appointed Dr Taylor convenor and then separated at a late or rather early hour’ (NS, 7 July 1838).

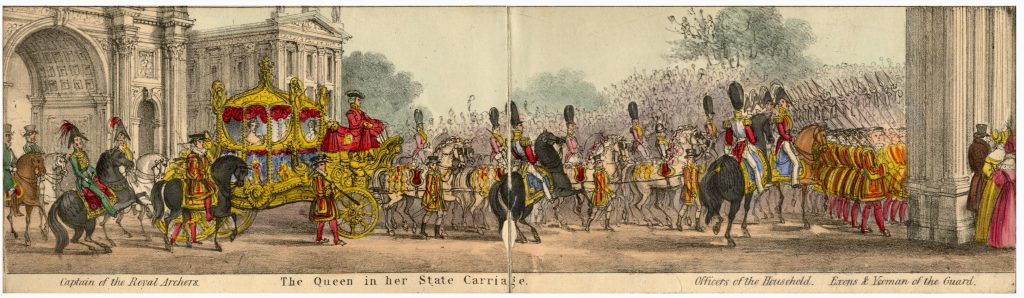

© British Museum. Click for larger image.

But the radicals did not have it all their own way. At Elland near Leeds, a town with a strong radical reputation, ‘fifty boys mounted on horseback attempted to form a procession in honour of her Majesty’; they were joined by Sunday School children and ‘having walked a short distance for a little juvenile amusement, they at last concluded by singing “God save the Queen,” in full chorus’. The Star’s disgusted correspondent noted: ‘The sensible part of the inhabitants took no share in the proceedings. The leaders of the van were two men who are said to be rather daft.’

Perhaps surprisingly given the Northern Star’s general scepticism, the paper also carried reports of coronation celebrations in Rochdale and Halifax which were wholly uncritical, and in a subsequent issue, the Star carried a request from the Elland radical Richard Grassby to say that the local celebrations had been rather grander than the paper had suggested (NS, 21 July 1838). The editor excused himself, explaining that he had relied on a report submitted under ‘the authority of a respectable signature’.

Reliant as he was on reports from numerous unpaid correspondents to fill the paper’s pages, editor William Hill may have thought it best not to upset his more royalist contributors by rejecting their copy. He may well also have been aware that activist opinion was most likely at odds with the views of many of the rank-and-file. ‘For most Chartists,’ argues the historian Paul Pickering, ‘the queen was not the problem’; indeed, ‘many Chartists were prepared to build their campaign for democracy around the monarchy’.

Despite this, the republican flag of red, white and green horizontal stripes carried by the Spencean ultra radicals at Spa Fields in 1816 was still widely in use throughout the Chartist period, and for years after the coronation. In 1842, a Manchester manufacturer offered tricolour silk scarfs for sale at 4s 6d each (NS, 5 March 1842); six years later, the Star carried a poem titled ‘The Chartist Tricolour’ (8 April 1848); and at celebrations to mark the second anniversary of the O’Connorville land settlement, ‘The Chartist tri-coloured flag was “fluttering in the breeze” from many of the allotments, as well as the larger flag from the dome of the schoolhouse’ (NS, 5 May 1849). For the funeral of ‘the late political martyr’ Alexander Sharp, who died in London’s Tothill-fields prison later that same year, the coffin was ‘covered in a pall of scarlet velvet, having a satinette double border of white and green, thus forming the Chartist tricolour’, reported the Star (29 September 1849).

With the coronation out of the way, the Star had editorialised (30 June 1838): ‘The farce is over – the “idle and useless pageant” has gone by – the doll has been dressed, dizened, and exhibited – a host of gawping idlers have been gratified with a spectacle.’ But, it asked, ‘Now, that we have time to breathe, let us enquire “why was this waste made?” What single benefit is likely to accrue, either to the Queen or to the Country, from this idle show – this obstruction of public and private business – and this palpable waste of the national resources, at the precise moment when we are up to the very neck in the mire of national bankruptcy.’

It concluded: ‘We love the Queen. We desire not that her reign should be one of anarchy and ruin, and therefore, we boldly tell to her the truth. The nation is beggared. The poor are starving. The people are discontented. Their just complaints become louder and louder every day. Their long tried patience is fast waning, and unless justice be done by returning to the first principles of that constitution which she has sworn to uphold, inviolate, and the laws be made BY ALL for the benefit of all, a mighty whirlwind overhangs the fine prospects of this empire, whose fearful vengeance no power can avert.’

It was stirring and heartfelt stuff on the part of the Star’s editor. The effect of which was surely only slightly lessened by the fact that almost the entirety of the paper’s facing page was given over to a report of the coronation in all its pomp, pageantry and ritual.

Further reading

‘Republicanism in nineteenth century England’, by Norbert J. Gossmann, in International Review of Social History, vol 7, no 1 (1962) pp47-60 (on JISC)

‘The Hearts of the Millions’: Chartism and Popular Monarchism in the 1840s’, by Paul Pickering, in History, vol 88, no 2 (290) (2003), pp227-248 (on JISC)

All newspapers cited above can be found in the British Newspaper Archive.

Data on coronation spending is taken from The Coronation: History and Ceremonial, House of Commons Library Research Briefing, by David Torrance (26 April 2023