Petition on behalf of the Chartist prisoners, 1841

Chartism is defined by the three great petitions to Parliament of 1839, 1842 and 1848. What is often overlooked is that there was a fourth petition on behalf of the Chartist prisoners, collected in the spring of 1841 and presented to MPs in such theatrical style that it is hard to see how it has been largely forgotten.

Furthermore, this fourth great petition was rejected by the House of Commons only on the casting vote of the speaker.

This is one of a number of articles dealing with the Petition for the Prisoners. See also:

Full text of the Petition for the Prisoners, 1841

One of the priorities of newly formed National Charter Association had been to continue the campaign for a pardon for John Frost, William Jones and Zepheniah Williams, the leaders of the Newport uprising, who had been sentenced to transportation for life to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania). They also wanted the release of the numerous Chartists rounded up and imprisoned in 1839 and 1840, many of whom had bee sentenced to hard labour.

Quietly, over the spring of 1841, while both William Lovett and Feargus O’Connor were in prison, and with none of the arguments that had accompanied the collection of names for the petition of 1839, the Chartist movement accumulated 1,339,298 signatures seeking the release of the prisoners, the return of the exiled Newport leaders, and a pardon. This was more names than had been collected in 1839 and included the signatures of a significant number of women.

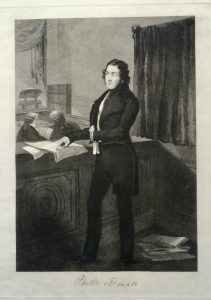

Much of the credit for masterminding the drama of the event when the petition was carried from the Old Bailey to Westminster must go to the radical MP for Finsbury, Thomas Slingsby Duncombe (pictured left), who would go on to be the Chartist movement’s greatest ally in the House of Commons.

Here is how Peter Murray McDouall reported the events of 25 May 1841 in McDouall’s Chartist and Republican Journal (note, additional paragraph breaks have been inserted for ease of reading):

THE FUSTIAN JACKETS AND THE NATIONAL PETITION

It will be a memorable day in the recollection of everyone concerned in carrying down the gigantic mass of signatures to the House of Commons on Tuesday the 25th day of May, 1841. Previous to the appointed day, roll after roll arrived and were added to the parent sheet. There seemed to prevail a universal enthusiasm throughout the nation, and when the numbers were proclaimed, 1,300,000 signatures, on the morning of the 25 th , the cheers resounded through the Old Bailey, and rolled away in its granite recesses.

Eighteen stone-masons, principally from the New Houses of Lords and Commons volunteered to carry the mass down, and preparatory to the march a meeting was held in an adjoining tavern. The men were in high spirits, and on eight names being called they filed out like soldiers, and capital ones they would have made.

Our little room, 55 Old Bailey, was crowded to suffocation, and the street blocked up. With some difficulty, the eight masons, attired in clean white fustian jackets, got admission, and the place being cleared of the strangers, a large frame was brought in, composed of two long beams of wood, supporting a cup like a socket the size of the immense role. It was like the end of a tun sawed off, into which the equally tun-like petition was placed, then completing the resemblance.

At a quarter-past-three we got under weigh, the Members of the Convention marching three abreast in front, and a vast procession three and three in the rear. Eight masons bore the mass on their shoulders, and eight more walked side by side to relieve the bearers at intervals. The weight was so unexpected that frequent stoppages and changes of hands ensued.

The spectacle attracted great attention, from the ragged street sweeper to the duchess with the golden eye glass. The city police behaved very favourably, but the metropolitan blues were very indifferent. The omnibus drivers were very rough and violent. We marched down, slow march, through Fleet-street, the Strand, past Charing Cross, the Horse Guards, and to the Parliament House. The windows of the public offices were particularly crowded, and great curiosity seemed to prevail.

The door of the house was finally reached, and around it there was an immense crowd awaiting. Then, but not until then, did the cheering commence. It began in front and rolled back along the line, and swelled louder and louder, until the thunder reached the inner House. Horses pranced and galloped off, carriages clanked together in confusion, and the astonished police ran together to defend the entrance to the house.

The fustian jackets were pushed into the doorway, and for a short time the immense mass stuck fast in the entrance, whilst the cheers rang along the passages and lobby, bringing out every member in the house.

The police drew their bludgeons, but were ordered by several individuals to put them in their pockets again, an advice very properly attended to, for certain am I that had a single blow been struck, the house would have been taken by storm, and the petition or a fustian jacket placed in the chair. The police belonged to the A division, and no doubt remembered how their roofs were untiled at Birmingham.

A message arrived for the petition to be carried into the lobby, and consequently the fustian jackets moved up the matted stairs, and along the entrance, through a line of strangers and Members of Parliament. In the lobby the usual order was upset and a great crowd besieged the door of the house itself, the great petition seeming like the head of a battering ram against the green base doorway.

Presently, Mr Duncombe appeared, and the mass being lowered and turned on its side, it was rolled on to the floor of the house like a mighty snowball, bearing with it the good wishes of all around, and 1,300,000 people’s blessings. The doors closed, order was restored, and the fustian jackets were ushered into the gallery.

The petition was presented, the debate began, finally a bell rang, and the Speaker cried out clear the gallery. All strangers rushed out, the doors were bolted, and whilst murmers of anxiety filled the passages the bolts creaked again, and out rushed the members. “How has it gone sir.” “Votes equal, 58 and 58.” “How has the Speaker given it.” “Against.” “Damn him.” Out rushed the members, and away went the strangers, leaving the house deserted by nearly all except the officers and understrappers.

This was the end of the march of the fustian jackets to the bar of the house; the forerunner of their appearance next time in the house through the representation, duly elected to serve them in the People’s Parliament, when justice will be granted without praying, and mercy established without asking. What next?