Alexander Sharp, 1821 – 1849

Alexander Sharp was imprisoned in 1848 after speaking at a series of meetings at Clerkenwell Green and Bishop Bonner’s Fields in east London. He died in prison the following year, murdered, said the Chartist movement. This is the story of one of the Bethnal Green Chartist Martyrs.

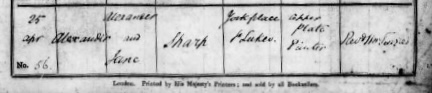

Alexander Sharp was born in April 1821 in the City of London Lying-in Hospital, one of several such charitable institutions dating to the middle of the previous century intended for the ‘wives of poor industrious Tradesmen or distressed House-keepers’. Baptismal records show that his parents Alexander and Jane lived at York-place in the parish of St Luke’s in Finsbury, just outside the City’s borders.

Alexander followed his father into trade as a copper-plate printer – an occupation requiring both skill and physical strength. Copper-plate printing had been used for centuries to produce prints and book illustrations, but by the 1830s it was in sharp decline as publishers switched to steel-plate engravings; and it is likely that Alexander would have struggled to find well-paid work.

Aged nineteen, on 18 October 1840, he married Eliza Smyth at St Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch. Six months later, when the census was taken on the night of 6 June 1841, the young couple were living at Turnmill Street in Clerkenwell (an area of Finsbury) with their three-month-old son, also named Alexander. Eliza was still just fifteen years old.

The first mention of Alexander Sharp’s involvement in Chartism comes in 1843, when the Northern Star’s list of those nominated to the General Council of the National Charter Association has an entry for Clerkenwell that includes seven names, among them, ‘Mr Alexander Sharp, printer, 5 Taylor’s Row’. Conceivably this could be either Sharp or his father; but there is no other mention of the elder man having any political involvement, so this is most likely the younger Sharp, then 21 years old.

He was certainly the Alexander Sharp who in May 1848 was elected as one of two delegates from Tower Hamlets to the National Assembly, and who was nominated as one of twenty ‘national commissioners’ to work alongside the newly elected executive committee (NS, 3 June 1848). The same issue of the paper also records that he delivered a lecture on the NCA’s new organisational plan at the Royal Oak, Turville-street, Bethnal Green.

And in that same month he emerged as a fiery platform speaker.

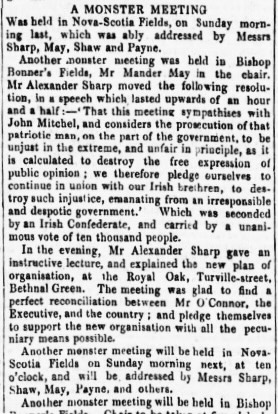

As London’s Chartist and Irish Confederate groups began to co-operate more closely, Alexander Sharp was among the speakers at a meeting on Clerkenwell Green in support of John Mitchel, editor of the United Irishman, who was then on trial in Dublin under the new Treason Felony Act. It was for his part in this 26 May meeting that Sharp and his co-accused Joseph Williams would later be arrested.

But in the mean time, and with Mitchel sentenced to transportation, on 30 May Sharp would again speak at a meeting of Chartists and Confederates on Clerkenwell Green. The series of meetings culminated on 4 June, when Sharp spoke first at a meeting at Novia Scotia Gardens and later that same day before a considerably larger crowd at Bishop Bonner’s Fields alongside Ernest Jones and others. That meeting would end in rioting on the part of both demonstrators and police.

Over the following week, Sharp would be picked up and charged with sedition for his speeches at Clerkenwell Green on 26 May and at Bonner’s Fields on 4 June. Williams was charged for his speeches at Clerkenwell Green on 25, 26 and 29 May. Joseph Green would face similar charges for his appearances at Clerkenwell Green on 25, 26 and 29 May. William John Vernon, John Fussell and Ernest Jones were arrested for similar offences at an overlapping series of meetings.

Sharp was brought up for trial on 3 July, where the court heard evidence from shorthand writers paid by the police to take notes of the meetings. One told the court that on 4 June Sharp had said:

‘I would not recommend any man to strike or insult a policeman, but if they strike or insult you, if there are not stones, there are better and more formidable weapons. You will often find about the streets of London plenty of railings before the houses; let every man only—when necessary grasp one, and all pull together, and you have then got a weapon better than any policeman's truncheon—it will take a policeman five or six times to strike a man before he quiets him with his truncheon: but only strike a policeman once with such a weapon as I have recommended, and you will soon silence him.’

He was found guilty of sedition and unlawful assembly, and sentenced to two years and two months in prison. Similar sentences were handed out to all those who had faced the court.

Locked up in Tothill Fields Bridewell, Sharp’s friends were at first able to pay the 5 shillings a week needed to exempt him from the requirement to pick oakum (the mind-numbing and painful task of separating strands of old rope by hand). This may have been an organised Chartist effort to spare him hard labour as Williams, too, benefited from similar payments in the first months of his imprisonment. But when the money ran out in August 1849, the deputy governor ordered him to work. Sharp refused, arguing that he had not been sentenced to hard labour.

As punishment, Sharp was put on a bread-and-water diet and in solitary confinement – robbing him of the opportunity for fresh air and exercise. With cholera already present in the prison, Sharp swiftly fell in, and within a fortnight he was dead (NS, 15 September 1849). He died a day after his fellow prisoner Joseph Williams – both, declared the Northern Star, ‘victims of the bread and cold water diet’.

The Sun, the leading liberal London evening paper of the time, was horrified. ‘Until the law be modified in some measure the public will be liable to hear of repeated instances such as those of poor SHARPE and his companions – men subjected to treatment so cruelly superfluous that they are driven into the jaws of death through the ghastly medium of the Asiatic Cholera’ (20 September 1849).

The Northern Star (22 September 1849) declared both men to be ‘martyrs to the cause of political freedom’.

The Chartist body was heavily represented at the inquest held within the prison walls on 17 September. Alongside Captain Williams, the Inspector of Prisons, and Henry Pownall, chairman of the Middlesex Magistrates, were: ‘Thomas Clark, James Grassby, and Edmund Stallwood on behalf of the Chartist Executive; Messrs Millar and Stills on behalf of the Committee of Metropolitan Delegates, sitting at 28, Golden-lane, Barbican; Tindall Atkinson, Esq, Barrister-at-law, also attended as the professional agent of the National Victim Committee.’

After hearing a lengthy account over two days of Sharp’s time in prison, his refusal to pick oakum and the punishment that followed, and the prison surgeon’s evidence, the jury delivered its verdict that Alexander Sharp had died of Asiatic Cholera. One jury member, Mr A Flanes of 28 York Street, Westminster, refused to sign the verdict unless a strong censure of the prison authorities was added, ‘but in consequence of the jury consisting of sixteen persons, of course the one dissentient did not invalidate the verdict’.

Still only 26 years old at the time of his death, Sharp left a widow and three young children.

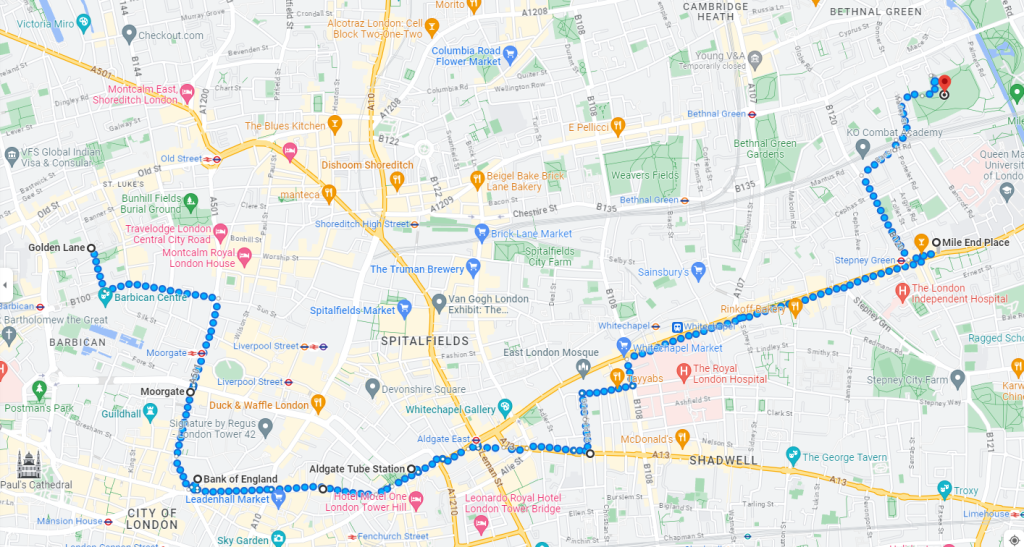

Sharp’s funeral took place on Sunday 23 September, ‘and notwithstanding the extreme wetness of the morning, a vast concourse of persons attended from all parts of the metropolis and its environs’ (NS, 29 September 1849). The ‘mournful procession’ set out from the Chartist meeting-place at 28 Golden-lane. Marching behind Mr Fowler as marshalman were banner bearers carrying the Finsbury tricolour flag, eight men with wands, and a plate-glass manufacturer’s van which formed a raised dias on which was the coffin.

The coffin itself was covered with ‘a pall of scarlet velvet, having a satinette double border of white and green, thus forming the Chartist tri-colour’. On the sides of the van was inscribed in large black letters, ‘He asked for freedom with his breath, Merciless tyrants gave him death’, and at its back was the inscription ‘No man should be a felon for his political opinions’.

‘On either side of the van were men with the batons of office to clear the way. The van was followed by twelve friends of the deceased, bearing the wands of office; immediately behind them was the magnificent flag belonging to the “Emmet brigade” emblazoned with the harp of Erin, and inscribed – “What is life without liberty.” This was followed by several cabs, bearing the widow, orphans, and other relatives of the deceased; the rear was brought up by a long line of political friends, walking arm in arm, four and six abreast.’

The procession wound its way out of Finsbury Square by way of the Pavement, Moorgate Street, past the Bank of England and east along Leadenhall-street, Aldgate, through Mile End-gate and on to the Victoria Cemetery (see map). The cavalcade took two and a half hours to reach its destination, and though fewer people were prepared to tramp through the muddy streets than had accompanied Williams the previous week, ‘the roads, windows and balconies were lined with sympathising spectators’, and on arriving at Whitechapel, they found that ‘the immense width and length from Aldgate to Mile End-gate presented a forest of densely crowded human beings’.

The Star reported: ‘We have it on the assurance of an inspector of police, that there could not have been less than 30,000 persons in the cemetery alone.’

Mr Dixon gave the funeral oration, urging those at the funeral – and most likely with the wider movement of Chartists who would later read his words to support the families of Sharp and Williams. ‘Let me remind you that it now becomes your duty to be husbands to the widows, and fathers to the fatherless. Remember they have lost their all in your cause – their husbands fell in the struggle for y our emancipation, and therefore they have a just demand upon you for support; they have lost that prop to which the loving wife clings as the Ivy clings to the Oak. And oh! Let me implore you not to let them in addition to the irreparable loss they have already sustained, be subject to the cruelties of the Poor Laws, but set to work at once, and put them in the way of getting a livelihood for themselves and little ones.’

A poem composed by the leading London Chartist John Arnott was then sung over the grave, and Edmund Stallwood declared the proceedings closed – imploring the vast crowd to depart peacefully and in ‘processional order’ so that each might have an opportunity to drop their subscriptions into the collecting boxes. The Northern Star would later report that ‘a very considerable sum was raised’.

Donations for the families of Sharp and Williams continued to be reported by the Star for some time to come. The two lawyers engaged to represent the National Charter Association at the men’s inquests returned 8 guineas from their fees for the families; small sums of a few shillings or pennies a time were noted week by week; and a concert and ball held in the Waterloo Rooms in Edinburgh raised eight or nine pounds.

There would also, in time, be a monument to the Bethnal Green Chartist Martyrs. But that is another story – told here.

Sources and further reading

‘The London Democratic Association 1837-41: A Study in London Radicalism’ by Jennifer Bennett in The Chartist Experience: Studies in Working Class Radicalism and Culture, 1830-1860, edited by James Epstein and Dorothy Thompson, Macmillan, 1982.

London Chartism, 1838-1848, by David Goodway, Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Copies of the Northern Star and Sun newspapers quoted above can be found in the British Newspaper Archive.

Baptismal and census records for Alexander Sharp can be found on Ancestry.

Old Bailey Proceedings Online, July 1848, trial of Alexander Sharp (t18480703-1712)