Robert LeBlond, 1816 – 1863

Robert LeBlond drew political inspiration from the radicals and freethinkers of the 1790s, and was a significant figure in secularism. In the 1850s he also provided an important bridge between the remnants of the Chartist movement and the emerging Liberal Party.

Robert LeBlond was born in London on 4 September 1816 and baptised at St Dunstan’s Church on Stepney High Street. His father declared his occupation at the time as ‘artist’ and would later describe himself as a ‘gentleman’. Robert was put to learn his trade as a copperplate printer with Thomas Brooker, most likely when he was fourteen, and would have served a seven-year apprenticeship. In November 1837, aged twenty one, he married Brooker’s sister Sarah.

LeBlond’s family had been Huguenot refugees, leaving France for England in the 1680s; he was at least the sixth generation of LeBlonds to be named Robert, and in due course would pass the name on to his own eldest son. Like many Huguenots who settled in Spitalfields in the late seventeenth century, the LeBlonds had connections to the textile trade. Unlike most of the East End silk weavers who traced their ancestry back to the original French refugee community, however, the LeBlonds appear to have been relatively successful in business.

LeBlond in Chartism’s first wave

Robert LeBlond must have been involved in the Chartist wave of 1838 and early 1839 when the first great petition for the Charter was presented to Parliament, but his name only appears in print in connection with the cause that summer, when he wrote to the Northern Star as secretary of the General Metropolitan Charter Association (15 June 1839, p6). This had been formed as a coordinating body for London’s many local radical associations, and it is not clear to which affiliated group LeBlond belonged.

Like other groups, Chartists typically met in public houses. LeBlond, however, complained that over the previous month, licensed victualers had ‘shut and locked their doors to us’. Though notorious for their opposition to radical causes, publicans were often prepared to overcome that distaste in pursuit of profit. In the wake of the Chartist disturbances of 1839, however, they were also susceptible to pressure from the authorities and feared that such tolerance might lead to the loss of their drinks licence.

LeBlond and the London Chartists proposed that working men should in future take their refreshment ‘at their own firesides’. They should refuse to enter the premises of any licensed victualer who would not subscribe to the principles of the People’s Charter, and collectively support the setting up of Charter Coffee Houses and halls ‘where we may not only meet and discuss the prominent political questions of the day, but where our children may be educated, and to which the rising generation may point as to memorials of the wisdom of their fathers’.

Taking care of business, and family

Curiously, there is no further mention of LeBlond in the Northern Star or any other Chartist newspaper, or in relation to any further involvement in Chartism for another decade. In effect, he appears to have sat out the entirety of the 1840s, emerging once again only once the Chartist cause was in terminal decline.

Most likely, LeBlond preferred to devote his time to his growing family and to building his business. He and Sarah would have four children in the space of five years: Emily (born 1839), Robert Emmet (1840), John Frederick (1842), and Sarah Alice (1844). Their eldest son was clearly named in the family tradition, but there was also a nod to LeBlond’s politics: Robert Emmet, a noted Irish republican, had been executed in 1803 after an attempted insurrection in Dublin.

In 1840, Robert and his brother Abraham had gone into business together as copperplate printers, setting themselves up in premises in Walbrook in the City of London, a little to the East of St Paul’s Cathedral. Their business took off after 1849 when they were granted a licence to use the Baxter Process, which enabled brightly coloured prints to be produced cheaply for the first time. Their more than 100 surviving prints include royal and religious scenes, the Great Exhibition of 1851, and some distinctly racier images with titles such as ‘The Queen of the Harem’ and ‘Is Anyone Looking?’ Many of the smaller prints were produced to be stuck to the lids of needle boxes and were printed in large runs.

Back into politics

Robert LeBlond kept a low political profile until 1850, when he was reported to have been on the platform at a meeting of Sir Joshua Walmsley’s National Parliamentary and Financial Reform Association (Morning Herald, 8 January 1850, p3). A former Mayor of Liverpool, Walmsley had been elected as a Liberal MP the previous year, and founded the organisation to campaign for his political causes – most notably a limited extension of the right to vote to all male ratepayers. However, it seems that LeBlond had maintained his more radical contacts: a report of the Association’s activities in The Weekly Despatch (28 April 1850) describes him as the ‘friend’ of the journalist and Chartist convert G.W.M. Reynolds, and shows them working together in an unsuccessful attempt to amend the Association’s programme in line with the more far-reaching Six Points of the Charter.

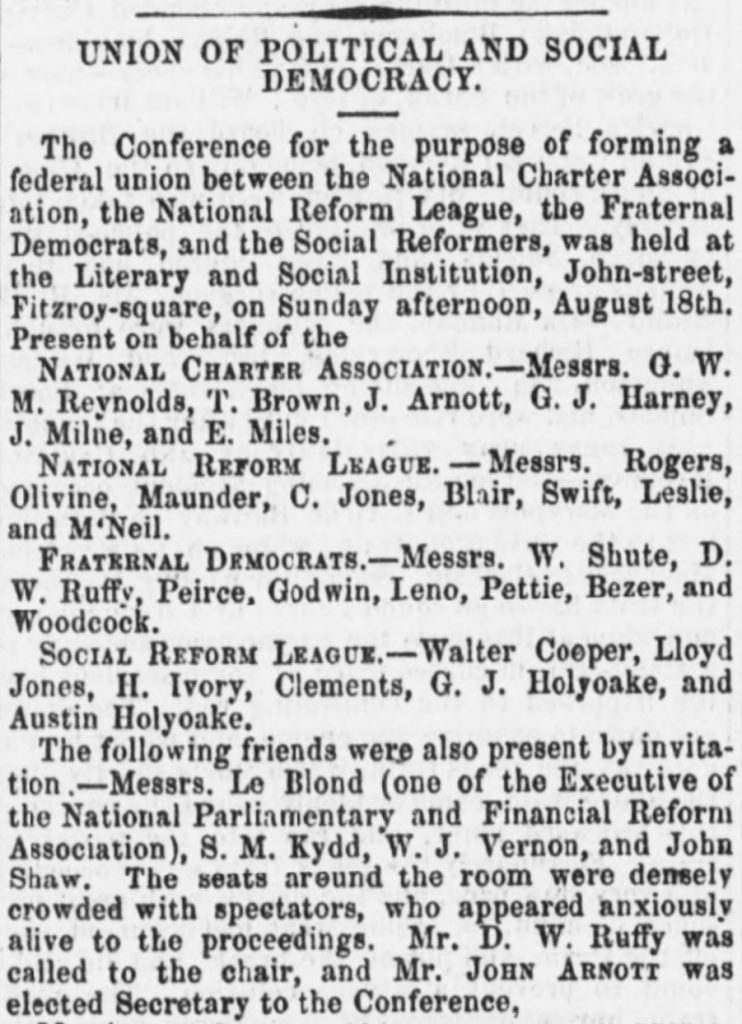

It was Reynolds who then reintroduced LeBlond to the Chartist movement, telling a meeting of the National Charter Association’s provisional committee that ‘M. LeBlond, a democratic friend of his’ wished to give £5 towards the legal costs of an arrested activist if others would match his donation (Northern Star, 1 June 1850, p8). It would not be long before LeBlond found himself at a conference called to unite the NCA and other groups (NS, 24 August 1850, p5). Within a matter of months the NCA executive committee had agreed to ask LeBlond to serve as their treasurer (Reynolds’s Weekly Newspaper, 29 December 1850, p8). He accepted, and became a regular presence at the committee’s weekly meetings.

Efforts to revive the Chartist agitation of earlier years achieved very little in practical terms. A convention in London on 31 March 1851 adopted a radical new socialist platform that combined the political demands of the past fifteen years with a programme that included nationalisation of the land, price controls and state education. But by the time LeBlond got back involved with the Chartist cause, it had long ceased to be the great popular movement it once was. An attempt to breathe new life into the old tactic of petitioning resulted in just 11,834 signatures – barely a fifth of the number achieved in 1849, and a tiny proportion of the millions that had been achieved in earlier years. But the NCA played an important role arguing the case for the full democratic programme set out in the Six Points of the People’s Charter amid a profusion of small, often short-lived groups supporting partial extension of the vote and other piecemeal political reforms.

Barriers to public office

Robert LeBlond had swiftly become a valued and leading member of both the National Charter Association and the National Reform Association – a precarious and unique balancing act given their past hostilities. But an entry into public life would not be as easy.

Early in 1851, there was a vacancy for the Walbrook Ward on the Court of Common Council, the City of London’s main decision-making body. A Mr Ingram Travers proposed LeBlond, ‘whose high moral character, business qualifications and personal integrity, were known to every member of the ward’ as a suitable candidate. But he also admitted being aware that ‘an objection had been raised to Mr LeBlond on account of his peculiar religious opinions’. (Morning Advertiser, 26 February 1851, p3). LeBlond’s opponents nominated a Mr Murrell to stand against him, declaring that Murrell was ‘a religious and thoroughly good man’. Though LeBlond ‘deprecated the introduction of religious tests for municipal office’, some of his supporters now abandoned him ‘on account of his ultra political and religious views’. And when a vote was taken the following day, Murrell defeated LeBlond by 34 votes to 11 (Patriot, 27 February 1851, p6).

There is no subsequent record of LeBlond seeking public office. He probably made no secret of either his political or his religious views. For alongside his Chartist and reform credentials, and despite the religious themes in much of the work put out by his print business, he was also a committed secularist and in 1853 a founder member of the London Secular Society. As the last vestiges of the Chartist movement dwindled to nothing, LeBlond turned his attentions to this cause.

Secularism and success

By 1851 the LeBlond family were living in one of the imposing three-storey villas that lined Crescent Road in Canonbury Park – a new development for successful businessmen looking to move away from the squalor of the city centre in search of a quieter life in leafy suburbia. In that year’s census, LeBlond described himself as ‘engraver lithography letter press, and copperplate printer employing 60 men & boys’.

Business was evidently good, and must have continued to improve. In August 1853, George Jacob Holyoake’s secularist newspaper The Reasoner reported that LeBlond had taken a fine mansion in Liverpool Street. LeBlond’s library reportedly included more than 3,000 books and periodicals; LeBlond offered to throw it open to members of the London Secular Society, and he and Sarah threw a soiree for some 70 or 80 members.

That September, LeBlond and Holyoake (who had coined the term secularism) set off on a lecture tour that took them from Newcastle to Aberdeen. Their progress can be traced in the pages of an often outraged local press, the Edinburgh News reporting that at Calton in Glasgow, ‘the main part of his [LeBlond’s] address consisted in the abuse of priests, Sabbath school teachers and the Christian mode of keeping the Sabbath’ (10 September 1853, p5).

LeBlond was as generous with his money as he was with his time in pursuit of secularism. In his much later memoir, Sixty Years of an Agitator’s Life, Holyoake recalled: ‘Mr LeBlond, in 1855 for several weeks gave me £10 every Sunday morning at South Place Chapel’ ostensibly as loans for Holyoake’s new secularist Fleet Street print house. ‘After the fifth morning I refused to take more.’That summer, LeBlond was among the delegates to a secular conference called by the London group with the aim of setting up a central board to coordinate the work of similar societies across the country.

However, LeBlond had not abandoned his commitment to parliamentary reform. When in 1854 Lord John Russell introduced a Bill to extend the vote, LeBlond told the council of the National Reform Association ‘that the Bill would confer the elective franchise upon not fewer than seventy-eight persons in his establishment who are at present without it; and we shall no doubt hear similar testimony from many other large employers in all parts of the country’ (The Patriot, 23 February 1854, p124).

Financial ruin and a new start

Sadly, things were about to go very wrong for Robert LeBlond. Early in 1856, creditors seized his house and library, and the LeBlond brothers’ partnership was dissolved. LeBlond is known to have been ill at this time, and it is possible that he was unable to meet his financial commitments as a result. The mansion in Liverpool Street may have overstretched his resources.

LeBlond’s bankruptcy was a blow for the secularist movement. The print business run by Holyoake had been acquired from the London radical and Chartist publisher James Watson, himself a secularist, on his retirement, and relocated from 3 Queen’s Head Passage to 147 Fleet Street at huge cost. LeBlond had promised Holyoake £1,000 but was unable to pay, leaving Holyoake with a huge debt that was not paid off until 1861. There was, however, clearly no sense that LeBlond was to blame for this: Holyoake even raised a loan against his own life assurance policy in order to help him.

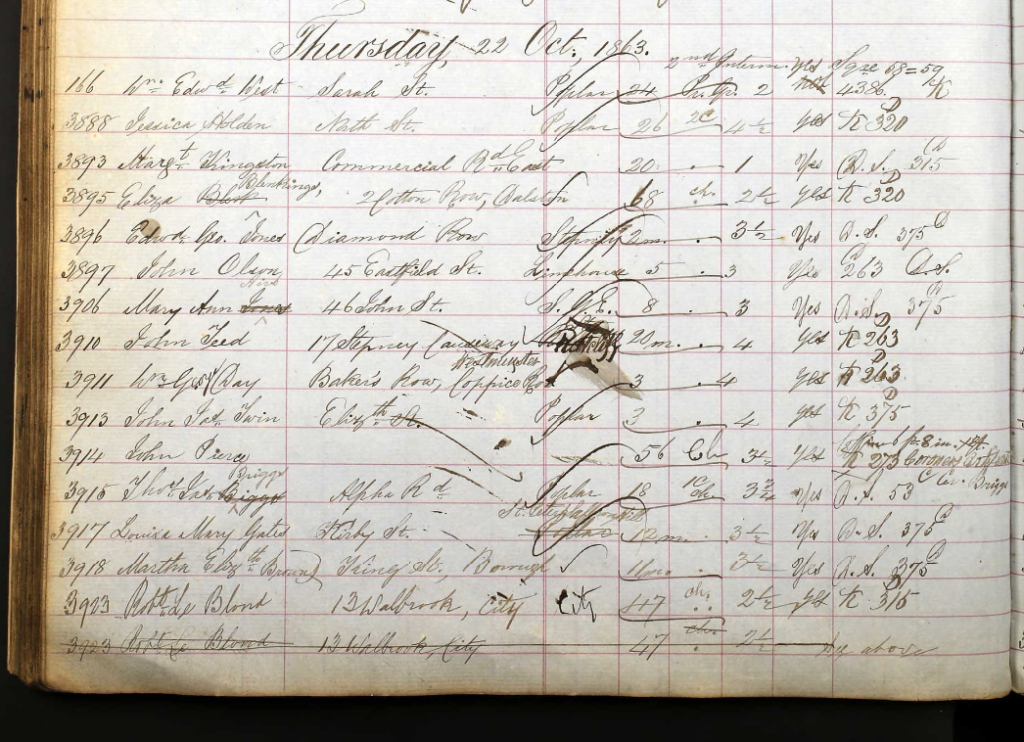

The financial disaster had family implications too. While Abraham continued to run the print business, Robert moved his family to the United States, where they settled in Cincinatti, Ohio. LeBlond found work as a bookkeeper and proof reader before attempting to start a new print business of his own. But in 1863, when this failed, he returned to London, leaving his family behind. Robert moved in with his brother in Walbrook, but was taken ill with dropsy (oedema), and died there on 18 October.

Robert LeBlond was buried in the City of London and Tower Hamlets Cemetery on 22 October 1863.

Inspiration and legacy

Robert LeBlond drew his political and religious inspiration from the radicals of an earlier era. In 1852, on the anniversary of Thomas Paine’s birthday he was among the speakers at a tea party and soiree held at the Literary Institution in Fitzroy Square to pay tribute to the great freethinker and revolutionary (Reynolds Newspaper, 8 February 1852, p14). And two years later he gave a toast at a sixtieth anniversary celebration marking the acquittal of Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and others of the London Corresponding Society on charges of high treason (Northern Daily Times, 9 November 1854, p4).

So it is no surprise that Chartism in its early years appealed to him: this was the revival of a democratic cause that had been forced underground during the wars with revolutionary and Napoleonic France, emerging only occasionally since, and meeting violent oppression when it did so – as at Peterloo in 1819. Chartism in the 1840s, however, was a working-class movement and sometimes a violent one. Physical force Chartism and the likes of Feargus O’Connor may have held little appeal for the increasingly successful businessman that LeBlond became.

As the movement declined however, LeBlond played an important role – along with G.W.M Reynolds and George Jacob Holyoake – in bridging the divide between the remnants of the Chartist movement and the middle-class reformers represented by Walmsley’s National Reform Association. In 1859, these reformers finally coalesced into an enduring Liberal Party, of which even Ernest Jones, the most radical of Chartist leaders, would become a member. Had Holyoake remained in London, it is easy to imagine that he too would have found his political home there.

Notes and sources

Newspapers referenced in the text can be found in the British Newspaper Archive. After the first mention, the Northern Star is given as NS.

Birth, marriage and death certificates, census entries and similar records are taken from Ancestry UK.

I am immensely grateful to Karen Furst for permission to reproduce the photograph of Robert LeBlond at the top of this page. She is Robert LeBlond’s third great granddaughter, and her website is an incredible resource. It includes (among much else):

- a Biography of Robert LeBlond (1816-1863);

- Genealogical information on the LeBlond family; and

- a transcription of The LeBlond Book: Being a History & detailed Catalogue of the Work of Le Blond & Co. by the Baxter Process, with a Glance at the other Licensees, by C. T. Courtney Lewis (Sampson Low, Marston & Company, 1920).

The GeorgeBaxter.Com website dedicated to the pioneer colour printer and his prints includes information on LeBlond & Co, and has a page of LeBlond prints for sale.

The two volumes of Sixty Years of an Agitator’s Life, by George Jacob Holyoake (T. Fisher Unwin, 1892) are available on the Internet Archive. Volume one, and Volume two.

Edward Royle’s book Victorian Infidels: The Origins of the British Secularist Movement, 1791-1866 (Manchester University Press, 1974) is a rich source of information on the secularist movement of the 19th century and of LeBlond’s role within it.